Results 1 to 1 of 1

Thread Information

Users Browsing this Thread

There are currently 1 users browsing this thread. (0 members and 1 guests)

-

02-15-2015, 10:25 PM #1

Hackers Hit 100 Banks in 'Unprecedented' $1 Billion Cyber Attack

Hackers Hit 100 Banks in 'Unprecedented' $1 Billion Cyber Attack: Kaspersky Lab

By Mike Lennon on February 15, 2015

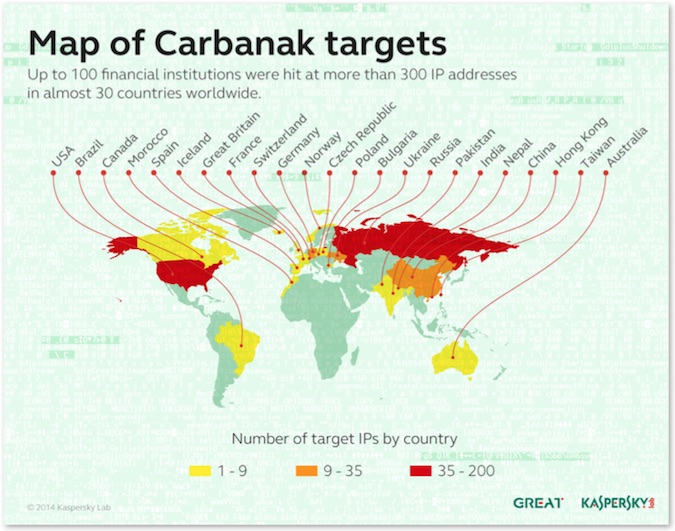

A multinational gang of cybercriminals infiltrated more than 100 banks across 30 countries and made off with up to one billion dollars over a period of roughly two years, Kaspersky Lab said on Saturday.

Kaspersky Lab, INTERPOL, Europol and authorities from different countries joined forces to to uncover the plot, which is being called an "unprecedented cyber robbery."

In a report obtained by SecurityWeek that is scheduled to be released Monday at Kaspersky Lab’s Security Analyst Summit (SAS) in Cancun, Mexico, researchers described a Hollywood style scheme where attackers used an arsenal of attack tools and techniques to siphon massive amounts of money directly from banks rather than targeting end user banking customers.

Through its investigations to date, the security company said it has evidence of roughly $300 million being stolen by the cybercriminals, but believes the total could be upwards of $1 billion.

The criminal gang, dubbed “Carbanak” by the Moscow-based security firm, appears to be a group of cybercriminals from Russia, Ukraine and other parts of Europe and China.

The attacks, which are still active, focused mainly on banks in Russia, but were also successful against banks in Japan, the Netherlands, Switzerland, United States and other countries.

In most cases, networks were compromised for between two to four months before the attackers made off with stolen funds, the 39-page report said, adding that during that period of time, attackers were able to get access to the right victims and critical systems and learn how to operate their tools and systems to execute the cyber heists.

The security firm estimated that the largest sums were grabbed by hacking into banks and stealing up to ten million dollars in each raid.

According to the report, one victim lost roughly $7.3 million due to ATM fraud, and another lost $10 million as a result of attackers exploiting its online banking platform.

The attackers were very familiar with financial services software and networks, according to Kaspersky researchers, and even programmed the malware to check victim systems for the presence of specialized and specific banking software.

"Only after the presence of banking systems was confirmed, were victims further exploited," the report said.

So far, attacks against approximately 300 IP addresses around the world have been observed on command and control servers analyzed by Kaspersky Lab.

In some cases involving ATMs, the hackers had direct remote access to the internal ATM networks which they used to remotely withdraw cash.

The criminals did not infect the ATMs with malware, but instead used standard utilities to control and test ATM equipment, the report said.

Not surprisingly, in all cases observed by Kaspersky Lab, the attackers used spear phishing attacks to infect systems with the Carbanak malware.

According to the report, the spear phishing emails contained attachments with weaponized Microsoft Word 97 – 2003 (.doc) and Control Panel Applet (.CPL) files. The malicious files exploit Microsoft Office (CVE- 2012-0158 and CVE-2013-3906) and Microsoft Word (CVE- 2014-1761) to execute shellcode, which decrypts and executes the Carbanak backdoor.

After compromising a system, the attackers install additional software such as the Ammyy Remote Administration Tool, or breach SSH servers.

Ammyy was a preferred tool for the attackers abecause it is white listed by many organizations for use by systems administrators.

While early versions of Carbanak were based partially on code from Carberp, the latest versions do not appear to use any Carberp source code, the report said. Source code for the Carberp Trojan was found for sale in the cybercrime underground back in 2013.

According to the report, the attackers were able to navigate internal networks and track down administrators’ computers for video surveillance, allowing them to see and record everything that happened on the screens of staff who serviced the cash transfer systems.

“In this way the cyber criminals got to know every last detail of the bank clerks’ work and were able to mimic staff activity in order to transfer money and cash out,” the company said.

Kaspersky researchers said that such video files were found on Command and Control servers. Sensitive bank documents were also found on servers controlling Carbanak, including classified emails, manuals, crypto keys, passwords and more. One file included key verification codes that are used by ATMs to check the integrity of the PIN numbers of its users.

“Once the attackers successfully compromise the victim's network, the primary internal destinations are money processing services, Automated Teller Machines (ATM) and financial accounts,” the report explained. “In some cases, the attackers used the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) network to transfer money to their accounts. In others, Oracle databases were manipulated to open payment or debit card accounts at the same bank or to transfer money between accounts using the online banking system. The ATM network was also used to dispense cash from certain ATMs at certain times where money mules were ready to collect it.”

“These bank heists were surprising because it made no difference to the criminals what software the banks were using. So, even if its software is unique, a bank cannot get complacent. The attackers didn’t even need to hack into the banks’ services: once they got into the network, they learned how to hide their malicious plot behind legitimate actions. It was a very slick and professional cyber-robbery,” said Sergey Golovanov, Principal Security Researcher at Kaspersky Lab’s Global Research and Analysis Team.

While the report goes into much greater detail, Kaspersky summarized how the money was stolen as follows:

1) When the time came to cash in on their activities, the criminals used online banking or international e-payment systems to transfer money from the banks’ accounts to their own. In the second case the stolen money was deposited with banks in China or the United States.

The experts do not rule out the possibility that other banks in other countries were used as receivers.

2) In other cases cybercriminals penetrated right into the very heart of the accounting systems, inflating account balances before pocketing the extra funds via a fraudulent transaction. For example: if an account has $1,000, the criminals change its value so it has $10,000 and then transfer $9,000 to themselves. The account holder doesn’t suspect a problem because the original $1,000 is still there.

3) In addition, the cyber thieves seized control of banks’ ATMs and ordered them to dispense cash at a pre-determined time. When the payment was due, one of the gang’s henchmen was waiting beside the machine to collect the ‘voluntary’ payment.

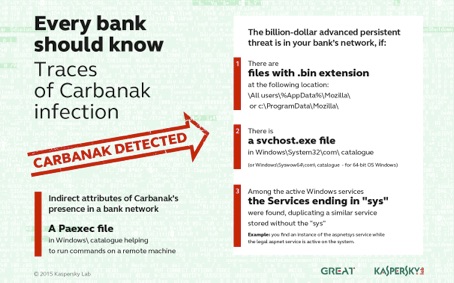

Kaspersky Lab said that based on their analysis, the Carbanak attackers are trying to expand operations to other Baltic and Central Europe countries, the Middle East, Asia and Africa. The company advised financial institutions to have a close look at their networks for the presence of Carbanak immediately.

The report does include an extensive list of Indicators of Compromise and additional details on how to scan and mitigate the attack.

According to the security firm, one of the best methods for detecting Carbanak is to look for “.bin” files in the folder:

..\All users\%AppData%\Mozilla\

Kaspersky also provided a .BAT script for detecting infections in its report.

“This is a jarring reminder of how easy it is for even sophisticated enterprises to overlook damaging changes to their cyber infrastructure,” commented Dwayne Melancon, CTO at Tripwire. “Malware leaves a trace when it compromises a system – even custom malware. Unfortunately, most of the times, that mark goes unnoticed because enterprises haven’t established a baseline, or known good state, and aren’t continuously monitoring for changes to that baseline.”

“Not only does this lack of awareness make it easier for criminals to gain a foothold, it makes it difficult, time-consuming, and very expensive to determine which systems can be trusted after-the-fact, and to determine how to remove the contaminated systems from the network,” Melancon added.

Additional details on Carbanak will be disclosed during a presentation by Kaspersky Lab researchers Sergey Golovanov and Sergey Lozhkin, and Peter Zinn, Senior Cybercrime Advisor for the Dutch National High Tech Crime Unit (NHTCU) at the Security Analyst Summit on Monday.

http://www.securityweek.com/hackers-...-kaspersky-labNO AMNESTY

Don't reward the criminal actions of millions of illegal aliens by giving them citizenship.

Sign in and post comments here.

Please support our fight against illegal immigration by joining ALIPAC's email alerts here https://eepurl.com/cktGTn

Similar Threads

-

France hit by unprecedented wave of cyber attacks

By JohnDoe2 in forum Other Topics News and IssuesReplies: 0Last Post: 01-15-2015, 02:17 PM -

Hackers Hit 5 U.S. Banks In Cybertheft

By JohnDoe2 in forum Other Topics News and IssuesReplies: 0Last Post: 08-27-2014, 08:20 PM -

Law enforcement websites under attack by hackers

By JohnDoe2 in forum Other Topics News and IssuesReplies: 0Last Post: 02-03-2012, 06:51 PM -

Cyber-Hackers Break Into IMF Computer System

By 93camaro in forum Other Topics News and IssuesReplies: 0Last Post: 11-14-2008, 05:42 PM -

World Bank Under Cyber Siege in 'Unprecedented Crisis'

By BetsyRoss in forum Other Topics News and IssuesReplies: 3Last Post: 10-13-2008, 12:18 PM

LinkBack URL

LinkBack URL About LinkBacks

About LinkBacks

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Giant Laken Riley Billboard Truck Circles Biden’s Speaking Venue...

04-23-2024, 09:52 PM in Americans Killed By illegal immigrants / illegals