Results 1 to 10 of 22

Thread Information

Users Browsing this Thread

There are currently 1 users browsing this thread. (0 members and 1 guests)

-

12-26-2015, 10:25 AM #1

US signs historic deal with El Salvador and Honduras for remittance securitization

I have posted this before and I am reposting for 2016. This is one of Hillary's accomplishments, it arranges for these countries to get loans based on what their illegals send home from the USA. why isn't anyone talking about this?

US signs historic deal with El Salvador and Honduras for remittance securitization

SUBMITTED BY SANKET MOHAPATRA

WED, 10/13/2010

The United States has recently signed separate Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) with El Salvador and Honduras to assist them in securitizing their future remittance receipts to raise financing for infrastructure and development projects. Under the Building Remittance Investment for Development, Growth, and Entrepreneurship (BRIDGE) initiative, banks in these countries will leverage their future remittance receipts to raise lower-cost and longer-term financing in international capital markets to fund infrastructure, public works, and commercial development initiatives (see press release).

In a speech in New York City on September 22, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton explained how BRIDGE would work to raise critically needed development funding:

“…Now, if they [migrants] send these remittances through the formal financial system, they create huge funding flows that are orders of magnitude larger than any development assistance we can dream of. By harnessing the potential of remittances, BRIDGE will make it easier for communities in El Salvador and Honduras to get the financing they need to build roads and bridges, for example, to support entrepreneurs, to make loans, to bring more people into the financial system…..Through BRIDGE and its in-country partners, local banks will be able to leverage their remittance flows….With the leverage from remittances, the local banks will be able to get lower-cost, longer-term financing for investments in infrastructure projects and small businesses.”

The financing structure proposed under BRIDGE is similar to that used by banks in several remittance-receiving countries such as Brazil, Jamaica, Kazakhstan, Mexico, Peru and Turkey, to raise over $15 billion in international financing during the last decade (see previous work on this topic by my colleagues Dilip Ratha and Suhas Ketkar on securitization of future-flow receivables and new paths to funding).

The BRIDGE initiative provides an excellent application of innovative financing instruments leveraging on migration and remittances. The World Bank group has recently become involved in this area.

The International Finance Corporation has recently provided up to $30 million debt financing for securitizing the significant remittances of El Salvadorans working abroad to raise financing for a credit cooperative Fedecredito. These additional resources will be used to increase lending to micro-entrepreneurs and low-income people in the country. Increasingly the Bank is receiving requests to assist countries to raise funds through diaspora bonds.

http://blogs.worldbank.org/peoplemov...securitization

Last edited by Newmexican; 06-30-2018 at 11:32 AM.

-

12-26-2015, 01:35 PM #2

I remember when you posted about this, Newmexican. It's disgusting. This was a move headed up by the drug cartels that own all these lousy politicians selling out our country.

A Nation Without Borders Is Not A Nation - Ronald Reagan

Save America, Deport Congress! - Judy

Support our FIGHT AGAINST illegal immigration & Amnesty by joining our E-mail Alerts at https://eepurl.com/cktGTn

-

12-29-2015, 02:57 AM #3

-

07-05-2016, 11:22 AM #4Share ThisNew Paths to Funding

FINANCE & DEVELOPMENT, June 2009, Volume 46, Number 2

Suhas Ketkar and Dilip Ratha

When financing is scarce, developing countries may try innovative approaches to raise capital

Developing countries have an outstanding short-term debt of nearly a trillion dollars. According to the World Bank, they face a financing gap of $370–$700 billion. Given the severe crisis of confidence in debt markets, it will be extremely difficult for countries to obtain private financing using traditional financial instruments. Innovative financing approaches are required, especially for private sector borrowers in developing countries, who face even harsher credit rationing than public sector borrowers.

Scarcity of capital threatens to jeopardize long-term growth and employment generation in many developing countries, which have limited access to capital even in the best of times. Official aid alone will not be adequate to bridge near- or long-term financing gaps. Ultimately, it will be necessary to use official funding to catalyze private flows to developing countries—adopting innovative financing approaches such as targeting previously untapped potential investors or using structures with credit enhancements to tap existing investors.

Stimulating such approaches is easier said than done, especially during the deepening financial crisis. But the debt crisis of the 1980s was ultimately resolved via an innovation—the creation of Brady bonds in 1989. Those bonds, named for then–U.S. Treasury Secretary Nicholas Brady, securitized the bank debt of mainly Latin American countries into tradable bonds that could be purchased by a broad investor base.

Some innovative market-based financing mechanisms that developing countries could use include borrowing from their expatriate (diaspora) communities, securitizing future revenues, and issuing bonds indexed to growth. Preliminary estimates suggest that sub-Saharan African countries could raise $5–$10 billion by issuing diaspora bonds and $17 billion by securitizing future remittances and other future receivables.

Diaspora bonds

The governments of India and Israel have raised about $40 billion, often during liquidity crises, by tapping into the wealth of their diaspora communities to support balance of payments needs and finance infrastructure, housing, health, and education projects. Diaspora bond issuance by the Development Corporation for Israel (DCI) has been a recurrent feature of that nation's annual foreign funding program, raising well over $25 billion since 1951. The State Bank of India (SBI) has issued diaspora bonds on just three occasions—in 1991, following the balance of payments crisis; in 1998, after the country conducted nuclear tests; and in 2000. The SBI has raised $11.3 billion. Jewish diaspora investors paid a steep price premium (perhaps better characterized as a large patriotic yield discount) when buying DCI bonds. Indians living abroad purchased SBI bonds when ordinary sources of funding for India had all but vanished.

The rationale behind diaspora bonds is twofold. For the countries, diaspora bonds represent a stable and cheap source of external finance, especially in times of financial stress. For investors, diaspora bonds offer the opportunity to display patriotism by helping their country of origin. Furthermore, the worst-case scenario for diaspora bonds is that debt service payments by the issuer are in local rather than hard currency. But because diaspora investors often have liabilities in their country of origin, they are likely to view the risk of receiving payments in local currency with much less trepidation than would nondiaspora investors.

Among countries with large diaspora communities are the United States (which has large groups from the Philippines, India, China, Vietnam, and Korea, in Asia; El Salvador, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Colombia, Guatemala, and Haiti, in Latin America and the Caribbean; and Poland, in eastern Europe), Japan (with a major diaspora presence of Koreans and Chinese), the United Kingdom (with large Indian and Pakistani communities), Germany (with people from Turkey, Croatia, and Serbia), France (with diaspora communities from Algeria and Morocco), and South Africa (home to migrants from neighboring countries in southern Africa). Large pools of migrants from India, Pakistan, the Philippines, Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Africa in the oil-rich Gulf countries are also potential purchasers of diaspora bonds.

If banks and other issuers want to tap the U.S. retail market, they likely will have to register their diaspora bonds with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, whose customary disclosure requirements could prove daunting for countries with weak financial institutions. But countries with a significant diaspora presence in Europe, where regulatory requirements are relatively less stringent, may be able to raise funds there. Diaspora bonds might also be issued in Hong Kong SAR, Malaysia, Russia, Singapore, and South Africa.

Future-flow securitization

Securitization is a much maligned term at present because the global crisis had its roots in securitized debt in the United States. Securitization, however, was not the main problem. It was overaggressive valuation of the underlying assets. As long as this error is not repeated and ample excess coverage is provided to allow for declines in the value of the underlying collateral, debt securitized by future hard-currency receivables will be a viable option for developing countries seeking to raise funds in the prevailing environment of low global risk appetite.

Ever since Mexico's Telmex undertook the first securitized transaction based on future U.S. dollar revenue flows, the main credit rating agencies have assessed more than 400 such transactions, valued at $80 billion. A wide variety of future receivables have been securitized—including exports of oil, minerals, and metals; airline tickets, credit card vouchers, electronic and paper remittances, and international telephone calls; oil and gas royalties; and tax revenue. Securitization of diversified payment rights (DPRs)—which include all hard-currency receivables that come through the international payments system—is a more recent innovation. DPRs are deemed attractive collateral because the diversity of their origin makes such flows stable. During 2002–04, when Brazil had difficulty accessing international capital markets, many Brazilian banks securitized future hard-currency DPRs to raise $4.9 billion.

By pledging future hard-currency receivables, securitized transactions subordinate the interests of current and future creditors. In a world of perfect capital markets, this might raise the cost of future borrowing and eliminate the principal rationale for securitization (Chalk, 2002). But many developing countries face capital markets that are far from perfect, and creditors may have trouble distinguishing between good and bad risks, paving the way for securitization.

Transactions backed by future revenue streams are structured so that the payments do not enter the issuer's home country until obligations to bond investors are met. Although this structure reduces sovereign transfer and convertibility risks, several other risks remain. These include:

• performance risk associated with the issuing entity's ability to generate the receivable,

• product risk associated with the stability of receivable flows because of price and volume fluctuations, and

• diversion risk if the issuer's government forces sales to customers not designated to direct their payments into the trust.

Many of these risks can be reduced through the selection of future-flow receivables and excess coverage. The latter has now become critical as a result of the recent dismal performance of mortgage-backed securities. Unlike the securitization of existing assets such as local-currency mortgage loans, future-flow securitization structures (involving foreign-currency export revenue or diversified payment rights) have held up very well during this financial crisis.

Still, issuance of securitized bonds is far below potential. Constraints include a lack of good receivables and strong (investment-grade) local entities and the absence of clear laws, particularly bankruptcy laws. There are, however, fewer barriers today than a decade ago.

Performance-indexed bonds

Debt service payments on fixed-coupon bonds can conflict with a country's ability to pay. When an internal or external shock cuts growth, revenue falls and social safety net expenditures rise. The resulting increase in fiscal pressure can force a country to choose between defaulting on foreign debt and adopting policies that increase the funds available for debt service but exacerbate the decline in output. Growth-indexed bonds are designed to overcome this problem. Coupons on such bonds are set to vary according to the growth performance of a country's gross domestic product (GDP), a proxy for its ability to pay. This feature lets a developing country follow countercyclical fiscal policy, paying less during an economic slowdown and more during an expansion. It is plausible that developing countries would be willing to pay a higher rate on indexed bonds than they would pay on fixed-coupon bonds to be able to avoid potential debt defaults.

This idea has been around for a while, but despite their apparent attractiveness, growth-indexed bonds have not caught on. Only a few developing countries—Argentina, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, and Costa Rica—have incorporated clauses or warrants that increase the payoff to bondholders if GDP growth exceeds a threshold. The GDP-indexed warrants in the Argentine program, for instance, represent the government's obligation to pay 5 percent of the excess annual GDP in any year in which the GDP growth rate rises above the trend. The market's initial low valuation of these warrants improved throughout 2007 as the Argentine economy posted strong growth.

Widespread use of growth-indexed bonds has been held back because of concerns regarding the accuracy of GDP data, the potential for deliberate underreporting of growth, and the complexity of the bonds. These obstacles are not overwhelming, but the liquidity of growth-indexed bonds has been low so far, and there appears to be a novelty premium (Costa, Chamon, and Ricci, 2008.

Similar to the growth-indexed bonds issued by sovereigns, subsovereign borrowers could issue performance-indexed bonds (PIBs). A PIB's coupon would be linked to a well-defined indicator of the performance of the borrowing entity. For a provincial or municipal government, for example, it could be a fiscal revenue target; for a public sector port authority, the indicator could be clearance or transit time; and for a private corporation, it could be earnings (Ramachandran, Gelb, and Shah, 2009). Such instruments have not yet been tested, but they seem potentially useful for large subsovereign borrowers in emerging markets.

Public policy issues

Like earlier financial innovations, diaspora bonds, future-flow-backed securities, and performance-indexed bonds facilitate access to funding for developing countries. Future-flow securitizations are designed to transfer credit risk from borrowers, thereby enhancing credit ratings and expanding liquidity. Diaspora bonds are meant to enhance liquidity. Growth- or performance-indexed bonds are designed to reduce credit risk by linking coupons to the ability to pay and to enhance liquidity by giving creditors an option on the performance of sovereign and subsovereign borrowers in developing countries.

Multilateral institutions and official donors can play an important role in promoting market-based innovations. They can provide credit enhancements to developing country borrowers facing severe financing gaps. They can offer technical assistance on legal frameworks, structuring, pricing, and risk management—and in the design of projects financed by innovative instruments. The institutions can help establish sovereign ratings, opening up access to international capital markets for poor countries in Africa, many of which are unrated (see box). They can also provide seed money to cover investment banking fees and rating costs incurred in structuring transactions supported by future-flow receivables. They may also offer partial guarantees on future flows to mitigate risk and catalyze private flows. They have a clear role to play in improving the accuracy and transparency of GDP data to support the issuance of growth-indexed bonds.

Sovereign ratings and market access

Developing countries’ access to credit markets is affected not only by the type of debt they are offering but by the quality judgments of the rating agencies, which, when applied to a nation, are called sovereign credit ratings. Sovereign ratings also provide a benchmark for subsovereign borrowers.

In general, sovereign debt spreads fall as sovereign credit ratings improve. But the major effect occurs when a rating rises to investment grade (see chart). Still, not having a sovereign rating may be worse than having a low rating. In 2005, foreign direct investment (FDI) accounted for 85 percent of private

capital flows to the 70 developing countries that have no rating. Bank loans made up most of the rest. In comparison, capital flows were much more diversified for rated countries—roughly 55 percent from FDI, 15 percent from bank loans, as much as 25 percent from bonds, and nearly 5 percent from equity flows. Even B-rated countries were better off. An examination of 55 unrated countries reveals that they were more creditworthy than previously believed: eight of those 55 countries would likely be above investment grade; another 18 would likely be in the B to BB category. This suggests that there is hope for some of the unrated developing countries to obtain financing in global capital markets. Access to debt, however, must be accompanied by prudential debt management practices. In addition, countries benefiting from the IMF and World Bank’s Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative and Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative should observe caution in taking on debt from opportunistic free riders.

This article draws on Innovative Financing for Development by Suhas Ketkar and Dilip Ratha, published in 2008 by the World Bank.

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/.../06/ketkar.htm

-

07-05-2016, 11:30 AM #5

The big banks are making money off of the remittances and they don;t want to lose that cash flow.

REMITTANCE PRICES WORLDWIDE

MAKING MARKETS MORE TRANSPARENT

HIGHLIGHT

Globally, sending remittances costs an average of 7.60 percent of the amount sent. This figure is used to monitor the progress of the global effort for reduction of remittance prices. Read our March 2016 report on global trends for remittance prices.

Globally, sending remittances costs an average of 7.60 percent of the amount sent. This figure is used to monitor the progress of the global effort for reduction of remittance prices. Read our March 2016 report on global trends for remittance prices.

Check the fees and Banks and businesses that are benefiting HERE

https://remittanceprices.worldbank.org/en

-

10-19-2016, 11:46 AM #6

Hillary has been incentivizing the illegals for years.

-

01-27-2017, 08:28 PM #7

Treasury under secretary for international affairs urges Trump to continue World Bank, IMF support

By Sophie Edwards

24 January 2017

Nathan Sheets, U.S. Treasury under secretary for international affairs. Photo by: U.S. TreasuryThe U.S. Treasury official for international affairs said it was important for the U.S. to “remain active” in multilateral institutions including the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, G20 and G7 during the presidency of Donald Trump.

Nathan Sheets was speaking at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington, D.C. His comments come amid fears the incoming administration could scale back U.S. support for multilateral institutions.

Trump has made threats against the United Nations, calling it a “club” for people to “have a good time.” Republican politicians have also put forward bills to reduce U.N. funding, or defund the U.N. entirely, unless the December 2016 U.N. Security Council resolution condemning Israeli settlements is reversed.

Sheets, whose role was to advise the treasury secretary on international economic affairs, including working with multilateral development institutions, described the IMF and the World Bank as “tools” that the U.S. will continue to “deploy” in the years ahead.

“When we think about what we can achieve with these multilateral mechanisms of engagement, the benefits from them are very, very significant and I think that that is clear to me, and that’s likely to be clear to others going forward,” he added.

As yet no replacement for Sheets has been named. The treasury secretary nominee is Steven Mnuchin, a former Goldman Sachs investment banker.

Discussing the World Bank, the under secretary said the institution is at the “forefront” of U.S. “efforts to address global poverty,” and referred specifically to December’s replenishment round of the World Bank’s International Development Association fund — which supports the bank’s work in the poorest countries — as an indicator of U.S. support for the institution.

More than 60 donor and borrower country governments, including the U.S., pledged a record $75 billion in IDA funding, in the last round.

Historically the U.S. has been the largest IDA contributor and is by far the biggest World Bank and IMF shareholder, wielding considerable influence over the institution’s strategy and policy and, controversially, over the appointment of the World Bank’s president.

Despite this fact, some “uncertainty” surrounds U.S. support for the institutions going forward, which could be demonstrated in the new administration’s refusal to honor the IDA commitment set by its predecessor, according to Scott Morris, senior fellow at the Center for Global Development.

The actual contribution will have to be approved by a Republican-controlled Congress, which is likely to take place in March, and so it would in theory be possible for the support to be scaled back or withdrawn.

However, although U.S. commitments frequently “never quite meet the full commitment pledged,” Congress is likely to meet the outgoing administration’s IDA pledge in order to maintain the United States’ reputation and leadership role, Morris said.

Sheets also praised the World Bank for its recent reforms, which he said have enabled the institution to spend its IDA balance sheet “more effectively.”

“Given the obvious constraints that we face in the U.S. and globally in financing multilateral development banks, it’s imperative that these institutions use the resources they have in as an effective manner as possible and we are seeing those kinds of reforms at the World Bank,” he said.

The incoming under secretary for international affairs is a “key appointment” and will have “very clear reach” to define the terms of the U.S. relationship to the MDBs, Morris said.

“It’s a highly consequential position which defines U.S. economic engagement in the world and is the focal point for policy engagement internationally,” he said.

It can also be a difficult position to fill — the post was vacant for a year before Sheets took office in 2014.

https://www.devex.com/news/treasury-...-support-89474

Support our FIGHT AGAINST illegal immigration & Amnesty by joining our E-mail Alerts at https://eepurl.com/cktGTn

-

01-27-2017, 08:30 PM #8

There has been no good at all come from the IMF for the US in my opinion. These are globalist socialist agendas. We need to end them all at some point, soon.

A Nation Without Borders Is Not A Nation - Ronald Reagan

Save America, Deport Congress! - Judy

Support our FIGHT AGAINST illegal immigration & Amnesty by joining our E-mail Alerts at https://eepurl.com/cktGTn

-

01-27-2017, 08:36 PM #9Support our FIGHT AGAINST illegal immigration & Amnesty by joining our E-mail Alerts at https://eepurl.com/cktGTn

-

06-19-2018, 08:16 AM #10

It is all about financing Central American countries at the expense of US citizens. Cheap labor from South American has diminished the job market and financial opportunities for the average US citizen in an EFFORT to build up corrupt,socialist latin american governments. IMO

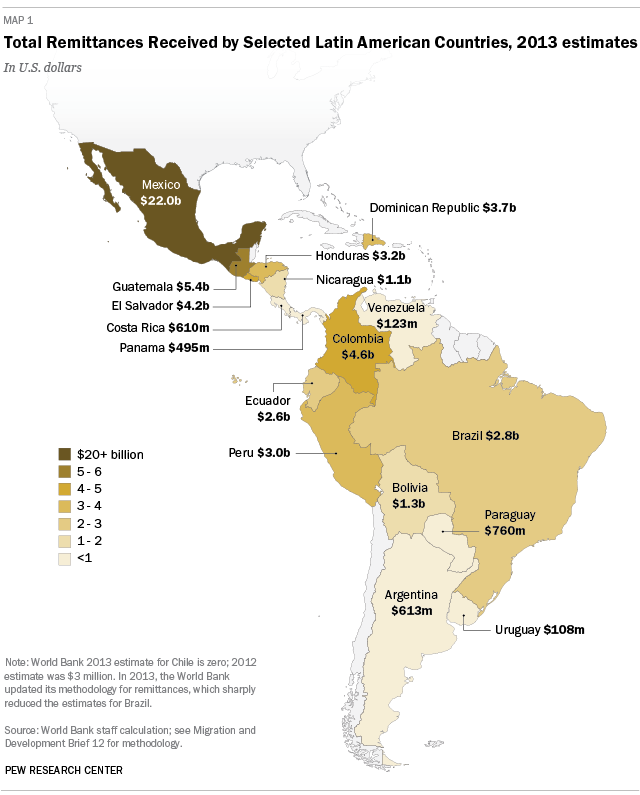

Report in 2013 three years after Clinton entered into the BRIDGE initiative.

NOVEMBER 15, 2013

Remittances to Latin America Recover—but Not to Mexico

BY D’VERA COHN, ANA GONZALEZ-BARRERA AND DANIELLE CUDDINGTON

1. Overview

Remittances to Spanish-speaking Latin American countries overall have recovered from a decline during the recent recession, with the notable exception of Mexico, according to World Bank data analyzed by the Pew Research Center.

Remittances to Spanish-speaking Latin American countries overall have recovered from a decline during the recent recession, with the notable exception of Mexico, according to World Bank data analyzed by the Pew Research Center.

Migrants’ remittances to Mexico, an estimated $22 billion in 2013, are 29% below their 2006 peak. For all other Spanish-speaking Latin American nations overall, the 2013 estimate of $31.8 billion slightly surpasses the 2008 peak.

Remittances from all sources to Spanish-speaking Latin American countries have more than doubled since 2000 but remain below their peak in 2007, the year in which the U.S. Great Recession began. The 2013 estimated total ($53.8 billion) is 13% below 2007’s $61.6 billion (in 2013 U.S. dollars).

The United States is the most important source of money sent home by migrants to the 17 Latin American nations as a group (including Mexico) that are the focus of this report. U.S. remittances accounted for three-quarters of the total in 2012—$41 billion out of $52.9 billion, according to World Bank data.

Mexico Falls, Latin America Overall Recovers

The decrease for Latin America overall was fueled by a falloff in remittances to Mexico, which receives more than 40% of all remittances to Latin America. If Mexico is excluded, remittance totals to Spanish-speaking Latin American countries as a whole have recovered after dropping during the U.S. recession years of 2007 to 2009. They bounced back in most of the other individual Spanish-speaking Latin American nations with remittances of more than $500 million a year. Of the dozen other nations, seven are estimated to have higher remittances in 2013 than during the U.S. recession years of 2007 to 2009.

Remittances to Mexico peaked in 2006, a year earlier than the recent high point for Spanish-speaking Latin American nations as a whole. Aside from a single-year increase in 2011, they have fallen each year since then. Other countries in which 2013 estimated remittance flows have not recovered from declines during the U.S. recession years of 2007 to 2009 are Argentina, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic and Ecuador.

Remittances to Mexico peaked in 2006, a year earlier than the recent high point for Spanish-speaking Latin American nations as a whole. Aside from a single-year increase in 2011, they have fallen each year since then. Other countries in which 2013 estimated remittance flows have not recovered from declines during the U.S. recession years of 2007 to 2009 are Argentina, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic and Ecuador.

However, in seven other Spanish-speaking Latin American countries, remittances either have rebounded from declines during the recession years of 2007 to 2009 or did not fall markedly during those years. In Bolivia, El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, remittances are estimated to be higher in 2013 than at their peak before the recession. In Nicaragua, Paraguay and Peru, remittances did not decline and have continued to rise.

The decline in remittances to Mexico—nearly all of which come from the U.S.—is linked to economic changes in the U.S., where one-in-ten Mexican-born people live (Passel, Cohn and Gonzalez-Barrera, 2012). The U.S. housing market crash hurt Mexican immigrants for whom the construction industry is a major job source, although a World Bank analysis concludes that the housing market’s link to remittance totals has weakened since 2011 (World Bank, 2013).

Another factor in the fall of remittances to Mexico could be the decline in the Mexican immigrant population in the U.S. since the onset of the recession, due to decreased arrivals and increased departures, including deportations. A Pew Research Center analysis of government data found that recent migration from the U.S. to Mexico equals and possibly exceeds migration from Mexico to the U.S. through at least 2012 (Passel, Cohn and Gonzalez-Barrera, 2012).

Remittance Patterns

Remittances: A Definition

“Remittances” are funds or other assets sent to their home countries by migrants, either themselves or in the form of compensation for border, short-term and seasonal employees (World Bank, 2013). Most funds come directly from migrants; compensation accounts for a single-digit share of remittances in most Latin American nations (World Bank, 2011).

Data in this report are provided by the World Bank and follow World Bank definitions adopted from the International Monetary Fund nations (World Bank, 2013). In some cases, trend analysis is restricted to nations with more than $500 million in annual remittances, where year-to-year trends are less volatile.

The World Bank reports only remittances sent via formal channels, such as banks and other businesses that transfer money. If unofficial remittances were counted, the total could be as much as 50% higher or more, according to household surveys and other evidence cited by the World Bank (World Bank, 2005).

In 2013, the World Bank revised its definition of remittances to delete a category of capital transfers between households. The World Bank also revised previously published numbers back to 2005 to reflect the change.

This change had a particularly large impact on Brazil, reducing the total remittance amounts considerably. It had less impact on other Latin American nations (World Bank, 2013). The 2013 estimates and the 2005-2013 trend data in this report employ the new definition. The 2005 and 2012 data on size of flows from one country to another have not been updated by the World Bank to reflect the new definition, so those may differ somewhat from trend data.

When reporting trends over time in remittance flows, amounts for years before 2013 are adjusted to 2013 dollars, using the average U.S. inflation rate for every preceding year. For this reason, some numbers in this report differ from unadjusted data published by the World Bank.

Remittances from the U.S. to Spanish-speaking Latin American countries are concentrated in countries closest to the U.S. border. Mexico alone receives more than half—$23 billion in 2012. The share rises to four-fifths when three adjacent countries are added in: Guatemala ($4.4 billion), El Salvador ($3.6 billion) and Honduras ($2.6 billion).

U.S. residents are the source of nearly all remittance money received in Mexico (98% in 2012) and of the majority of remittance money received in six other Spanish-speaking Latin American nations: Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Panama. Remittance amounts from the U.S. are higher than any other nation to three more countries, Colombia, Peru and Venezuela.

Spain, the next-largest sending nation to Spanish-speaking Latin American countries, contributed 8% of 2012 remittances, or $4 billion. Canada, which ranked third, sent 1% of remittances to these countries, or $704 million in 2012.

As is true of Latin America, the U.S. also is the largest source of remittances worldwide, sending a total of $123.3 billion in 2012, according to World Bank data. Saudi Arabia ($27.6 billion in 2012) is next, followed by Canada ($23.9 billion).

Among all countries, the largest recipient of remittances is India, with an estimated $71 billion in 2013. China ranks second ($60.2 billion), followed by the Philippines ($26.1 billion). Mexico ranks fourth.

Impact and Use of Remittances

Remittances are a larger source of money to Latin America than official foreign aid. In 2011, when foreign aid to Spanish-speaking Latin America nations totaled $6.2 billion, formal remittances were more than eight times that—$53.1 billion. Foreign aid totals less than remittances in each Spanish-speaking Latin American nation except Chile and Peru.

Remittances are a larger source of money to Latin America than official foreign aid. In 2011, when foreign aid to Spanish-speaking Latin America nations totaled $6.2 billion, formal remittances were more than eight times that—$53.1 billion. Foreign aid totals less than remittances in each Spanish-speaking Latin American nation except Chile and Peru.

Money sent home by migrants represents a varying share of the gross domestic product throughout Spanish-speaking Latin America. The highest shares are in three Central American nations, according to the World Bank: El Salvador (16.5% in 2012), Honduras (15.7%) and Guatemala (10.0%).

What is the impact of remittances? On the macro level, the World Bank has included remittance inflows in its measure of creditworthiness since 2009, so nations with high levels of formal remittances may be allowed to borrow more money than they otherwise could. At the household level, as might be expected, those who receive remittances have higher incomes, spend more and are less likely to be extremely poor than those who do not receive remittances (Ratha, 2013).

A significant part of remittances, often the majority, is spent on food, clothing and other day-to-day needs, according to research. Although there is variation by country, a significant, but smaller, share goes to saving and investment, especially among households that no longer include young children (Massey et al., 2012). Households that receive remittances also are more likely than those that do not to spend money on health care and education (Ratha, 2013).

A significant part of remittances, often the majority, is spent on food, clothing and other day-to-day needs, according to research. Although there is variation by country, a significant, but smaller, share goes to saving and investment, especially among households that no longer include young children (Massey et al., 2012). Households that receive remittances also are more likely than those that do not to spend money on health care and education (Ratha, 2013).

However, research is inconclusive about the impact of remittances on a receiving nation’s economy. Some studies have found that labor force participation declines in households that receive remittances, which hurts economic growth (Chami et al., 2003). Other studies focused on the impact of remittances in Mexico have found that at the state level remittances improve regional labor markets by raising employment levels (Orrenius et al., 2012).

The average cost of sending remittances to Latin America was 7.3% in late 2013, according to the World Bank, a decline from past years (World Bank, 2013a). The growing role of technology, especially mobile banking and online money transfers, has made it easier to send money home (Orozco, 2012). It also has made it easier, along with improved measurement methods by banks, for governments and central banks to track remittances. Lower costs, improved technology and better tracking have played a role in increasing the sum of formal remittances, and some research suggests that these factors, not fundamental economic changes, likely account for most growth in formal remittances over the 2000s (Orrenius et al., 2012)

Who Sends Remittances Home?

Remittance totals are strongly linked to the size of a particular country’s immigrant population in the U.S. and the share of its emigrants who live in the U.S. For example, the four Latin American nations that get the highest share of their remittances from the U.S.—Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras—also are the top four in terms of the share of their emigrants who live in the U.S. The Latin American nations with the lowest share of remittances from the U.S.—Uruguay, Bolivia and Paraguay—also have the lowest share of emigrants living in the U.S.

Remittance totals are strongly linked to the size of a particular country’s immigrant population in the U.S. and the share of its emigrants who live in the U.S. For example, the four Latin American nations that get the highest share of their remittances from the U.S.—Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras—also are the top four in terms of the share of their emigrants who live in the U.S. The Latin American nations with the lowest share of remittances from the U.S.—Uruguay, Bolivia and Paraguay—also have the lowest share of emigrants living in the U.S.

Most immigrants do send remittances home, and so do some people born in the U.S.; a Pew Research Center survey in 2008 found that 54% of foreign-born Hispanics and 17% of U.S.-born Hispanics say they send money to their home country (Lopez, Livingston and Kochhar, 2009).

Some research has found that foreign-born U.S. citizens and legal permanent residents are less likely to send remittances than unauthorized immigrants who may have less attachment to the U.S. and more to their home country (Massey et al., 2012).

This report is based mainly on data on remittances compiled by the World Bank, including overall trends for 2000 to 2013 as well as country-to-country flows for 2012. To add context to the remittance findings, the report also uses World Bank data on foreign aid and GNP, as well as 2012 estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey on the immigrant population in the U.S. from selected Latin American nations.

About this Report

About this Report

This report examines official flows of remittances, including overall trends from 2000 to 2013 as well as contributions from the U.S. in 2005 and 2012, with a particular focus on 17 Spanish-speaking nations in Latin America: Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela. Data also are included separately about Brazil. The data in this report, both for remittances and other economic indicators, are derived from the World Bank. Data on immigrant populations in the U.S. come from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. This report was written by D’Vera Cohn, Ana Gonzalez-Barrera and Danielle Cuddington. The authors thank Mark Hugo Lopez, Jon Cohen, Rakesh Kochhar, Jeffrey Passel and Paul Taylor for editorial guidance and data analysis and Dilip Ratha for supplying 2005 data about U.S. remittances to Latin America. Anna Brown number-checked the report. Marcia Kramer was the copy editor. Find related reports from the Pew Research Center’s Hispanic Trends Project online at pewresearch.org/hispanic.

A Note on Terminology

The terms “Latino” and “Hispanic” are used interchangeably in this report.

Unless otherwise specified, references to Latin America comprise the following Spanish-speaking countries: Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela. Cuba is not included because of lack of available data. Totals for Brazil are included separately.

“Remittances” include money sent via formal channels by migrants themselves, as well as compensation of employees working in other countries. Compensation generally accounts for a small fraction of the total. See text box on page 6 for more detail.

“Adults” refer to those ages 18 and older.

Read the rest at:

http://www.pewhispanic.org/2013/11/1...not-to-mexico/

Support our FIGHT AGAINST illegal immigration & Amnesty by joining our E-mail Alerts at https://eepurl.com/cktGTn

Similar Threads

-

US signs historic deal with El Salvador and Honduras for remittance securitization

By Newmexican in forum General DiscussionReplies: 13Last Post: 07-09-2015, 02:39 PM -

Senate Bill: Enough Green Cards for Everyone In Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador

By florgal in forum General DiscussionReplies: 1Last Post: 07-22-2014, 01:05 PM -

U.S. BRIDGE Initiative Commitments with El Salvador and Honduras

By Newmexican in forum General DiscussionReplies: 2Last Post: 04-11-2014, 07:30 PM -

Killings in el salvador dip, raising questions of a deal

By JohnDoe2 in forum illegal immigration News Stories & ReportsReplies: 0Last Post: 03-25-2012, 06:19 PM -

Sheriff`s deal in Honduras defended

By FedUpinFarmersBranch in forum illegal immigration News Stories & ReportsReplies: 2Last Post: 05-25-2008, 12:21 PM

25Likes

25Likes LinkBack URL

LinkBack URL About LinkBacks

About LinkBacks

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Watch: Paul, Hawley Torch Mayorkas To His Face On Laken Riley's...

04-19-2024, 02:32 PM in illegal immigration News Stories & Reports