Results 1 to 1 of 1

Thread Information

Users Browsing this Thread

There are currently 1 users browsing this thread. (0 members and 1 guests)

-

10-20-2015, 10:59 AM #1

Jay Dobyns fought the Hells Angels. Jim Reed fought the feds.

Jay Dobyns fought the Hells Angels. Jim Reed fought the feds.

THE ATF AGENT WANTED TO BRING AN UNBELIEVABLE CASE AGAINST THE U.S. GOVERNMENT. HE ONLY KNEW ONE ATTORNEY. BUT THAT ATTORNEY WAS MADE FOR THE JOB.

The federal agent needed a lawyer and quick, one who would believe his story — though he knew there was little reason for anyone to believe his story.

There had been a fire at the agent’s house just outside Tucson. It was arson. He figured it was set by somebody connected to the Hells Angels. After all, he had been undercover, infiltrated the outlaw biker gang, landed 50 arrests. A gang member would have a motive to burn down his house.

Instead, he said, his agency wasn’t looking at the bikers. It was looking at him.

The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, he said — the people who had employed him and sent him into the biker gang — now blamed him for the arson at his own home.

Jay Dobyns, who looked more biker than lawman, sat in front of a Phoenix attorney, telling him the case, telling him he needed a lawyer.That lawyer was James Reed, bespectacled, Ivy League educated and a specialist in construction law. He handled building contracts, construction defects — bone-dry matters that didn’t often get him into a courtroom.

Dobyns didn’t know Reed well. Reed was just the only private attorney he happened to know at all.

Dobyns wanted to sue the ATF, and quickly, hoping to stave off what he figured would be imminent arrest. And he wanted Reed to help him do it.Reed looked at the bearded biker-agent and considered the matter.

It would be an absurdly difficult case.

VIDEO AT LINK:

An attorney would have to argue that government agents were at best indifferent to one of their own at risk of being killed, possibly out of professional jealousy or spite. He would have to find proof the tale was true, have to pry evidence buried in federal records. No matter how hard he worked, Justice Department attorneys with bottomless resources would be trying to stop him.

But Reed knew one thing that Dobyns didn’t know: Though Reed did dry construction contract law, he was an attorney who had fought before. He had fought to prove the U.S. government wrong.

And before that, there had been the childhood years on crutches, the blood transfusions, the thing he had been fighting his whole life.

Reed thought about the tale coming from this trained federal investigator. The story was incredible; the case was impossible.

Reed didn’t know Dobyns well. But something made him feel that Dobyns was telling the truth.

Reed told Dobyns there were other lawyers more qualified to take the case. He would refer him to a list of names. They would be much better equipped to handle this.

But, deep down, Reed secretly hoped those more experienced attorneys would refuse the case.

If the government were truly treating its employee this way, Reed wanted to call them on it. He was ready for a fight.

A raw deal

An 8-year-old Jim Reed with Jimmy Carter. “I like your tie,” Carter told the boy.

An 8-year-old Jim Reed with Jimmy Carter. “I like your tie,” Carter told the boy.

Reed was born in 1963, a healthy baby who was missing one important thing: a protein called Clotting Factor VIII.

The condition is called hemophilia. The missing protein, the one most people have, is what helps cause blood platelets to clot.

Clotting stops wounds from bleeding uncontrollably. Without it, every time we scrape our knees as children, or cut ourselves shaving as adults, blood would spill out of those cuts and just keep spilling.

Reed doesn’t worry much about cutting himself shaving. The visible wounds aren’t the main problem for hemophiliacs. He can fix those cuts. The bleeding he worries about is internal. Non-hemophiliacs don’t think about this much, but blood vessels break all the time.

They break while running, while walking, while sitting, while rolling over in bed. High blood pressure can cause a tear.

For hemophiliacs, blood spills out of those tiny cuts, and just keeps spilling.

At its worst, the condition causes intense pain, akin, Reed said, to an ankle sprain anywhere in the body.

Reed was diagnosed when he was 6 months old. He had a cut lip that didn’t heal for days.

Reed used a wheelchair and crutches starting at around age 4. Blood swelling around his knees kept him from walking.

He was home-schooled in first grade because the classroom in his Atlanta school was located up a staircase he couldn’t climb.

Reed became the poster child for the Georgia bureau of the Hemophilia Society. He did photo-ops with the Atlanta Braves’ mascot and Georgia Gov. Jimmy Carter. Reed remembered he and Carter bonded over having the same name. They both also happened to be wearing pale blue neckties decorated with horses. “I like your tie,” Carter told the boy. A photo shows Carter and Reed clutching a gubernatorial proclamation. Reed is on crutches.

In October 1971, Jim Reed, age 8, met then-Georgia Gov. Jimmy Carter. Reed was the poster child for the Georgia chapter of the National Hemophilia Foundation.

In October 1971, Jim Reed, age 8, met then-Georgia Gov. Jimmy Carter. Reed was the poster child for the Georgia chapter of the National Hemophilia Foundation.

(Photo: Courtesy of Jim Reed)

Inside Reed’s body, the disease caused damage. The constant drips of blood altered the shape of Reed’s bones and cartilage. His muscles developed scars. His bleeds would cause swelling at his joints. At times, he said, his knee looked like a balloon.

Looking back, Reed said, he realizes how his family dealt with those visual horrors. They laughed.

Reed grew up in a climate of silly where the wordplay was quick and constant. When his mother prayed the rosary at the table, he and his siblings flared their nostrils to make one another laugh.

At the time, the treatment for hemophilia was to inject massive amounts of donated blood to deliver enough clotting protein. Reed’s father would visit a blood bank twice a month to donate and build up credits for his son. Treatments would require a day-long sojourn to the hospital.

But halfway through Reed’s childhood, scientists developed a way to separate the specific protein and concentrate it.

Blood still had to be taken from donors, and the final product still injected into hemophiliacs. But treatment could now be more frequent and administered at home.

In 1972, Reed flew to Los Angeles to test the new product. A year later, at age 10, he ran a mile for the first time in his life. “That’s the difference it made,” Reed said.

But that life-altering remedy came with a price.

Each dose of blood concentrate contained plasma from as many as 20,000 donors. And at the time, there was little screening of donated blood.

Reed kept up his injections, all through the rest of the ’70s, into the mid-’80s. He left behind his swollen joints and his crutches. He graduated from high school and went to Columbia University Law School.

There, in 1986, he was diagnosed with HIV.

Human immunodeficiency virus, the virus that causes AIDS, spread to as many as 50 percent of the country’s 50,000 hemophiliacs by 1985, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And, according to the National Hemophilia Foundation, about 90 percent of those who had severe hemophilia, like Reed, became infected with HIV.

For Reed, in 1986, this diagnosis meant a disease that was even less understood than hemophilia. More imminently, it meant fear of a disease that had no treatment and no cure. It also meant public fear, all around him.

Reed remembers the best example clearly.

In 1986, three brothers, Ricky, Robert and Randy Ray were barred from attending their public school in Florida. All three were hemophiliacs. All three acquired HIV through their plasma-concentrate injections. Their family had to take the school district to court to fight for the right to have their children attend public school.

After graduating from law school, Reed researched and wrote an exhaustive report on the medical underpinnings for the rise of HIV in the hemophilia community — and the legal reasoning that showed the government was at fault.

Key in his research was a memo from an FDA official that suggested the agency knew of the dangers, but was dragging its feet on screening the blood supply.

It was enough to convince key senators to pass the bill out of committee. Then public pressure caused the full Senate to pass the bill, known as the Ricky Ray Act, named after one of the brothers from Florida. It provided a fund of $770 million to compensate hemophiliacs who were infected with HIV between 1982 and 1987.

“My feeling is it wouldn’t have gotten out of the committee if we hadn’t done that report,” Reed said.

Reed began antiretroviral treatments to control his HIV. Despite living with HIV for nearly three decades, he has not been diagnosed with AIDS.

Reed moved to Phoenix in the 1990s, following his parents and grandparents. Homebuilding was a major industry in Phoenix and Reed found plenty of work involving the construction industry.

And though his life had been altered by a government failure, Reed never forgot the results of his report about the blood treatments. He remembers that he was buoyed by how Congress had responded. In time, Reed became more active in politics. He was a disability adviser to the Al Gore campaign in 2000 and would go on to work on the Barack Obama campaign two elections later.

Reed also never forgot about the Ray brothers, the three boys with HIV who had to fight the government for the right to go to school. Their family had gone to court, and won. At the end of the boys’ first week at the school, their home was consumed by an arson fire.

A fire in the nightReed first met Jay Dobyns in 2007. Dobyns was still working for the ATF. His house was still standing.

Dobyns’ home outside Tucson. (U.S. Department of Justice photo)

Dobyns’ home outside Tucson. (U.S. Department of Justice photo)

Reed had dabbled in entertainment law, including writing campaign platforms for the actress Morgan Fairchild when she ran for president of the Screen Actors Guild. A man in the office next to him, upon hearing that, wondered if Reed could help out a friend of his looking to sell his life story.

In 2005, Jim Reed worked on the campaign of actress Morgan Fairchild to be president of the Screen Actors Guild.

In 2005, Jim Reed worked on the campaign of actress Morgan Fairchild to be president of the Screen Actors Guild.

(Photo: Photo courtesy of Jim Reed)

If any federal agent’s life merited a movie, Dobyns’ did. The ATF claimed the undercover work of Dobyns and others involved in Operation Black Biscuit dismantled the Hells Angels — 50 arrest warrants, 16 indictments, including two for death-penalty eligible cases. Dobyns was named a “Top Cop” and was featured on “America’s Most Wanted.”

But the most serious charges did not stick. Some Hells Angels were ordered imprisoned for two to five years. But many were given probation. Many of those arrested never saw trial.

Death threats followed. Some were detailed and graphic. Dobyns, writing in his book “No Angel: My Harrowing Undercover Journey to the Inner Circle of the Hells Angels,” admitted that his time undercover made him paranoid. Still, he complained that the ATF was not doing enough to respond to the threats.

The ATF agreed. In September 2007, it reached a settlement with Dobyns, giving him $373,000 and a promise to monitor future threats.

Around the same time, agents in Arizona and Washington questioned whether Dobyns still needed his fake identity, and eventually ordered him to give up the documents that gave him cover.

In May 2008, the withdrawal was complete. Dobyns’ address became public record.

Three months later, while Dobyns was out of town, his wife heard a noise in the backyard. She thought about releasing the dogs, but kept them in the house. A neighbor would later tell her about a strange white van that had been parked on the street that day.

An arson investigator concluded that someone, at around 3:30 a.m., used “combustible material” to set ablaze a piece of furniture outside on the patio near a sliding glass door.

The heat shattered the window in the bedroom of Dobyns’ son. He scrambled to wake up his two sisters and mother. All escaped the brick house before it was hollowed out by fire.

Dobyns, who arrived back in Tucson later that day, was investigated as a suspect in the arson per routine. Two seasoned ATF agents cleared him.

Despite that, Dobyns was hearing that two supervising agents were continuing to target him as a suspect, ignoring other possible leads.

It was a story that could have easily been dismissed as paranoia. “No one would believe that our government would do that to someone,” Dobyns said.

Dobyns wanted to file a lawsuit, quickly. He visited the attorneys Reed referred him to, but none wanted the case.

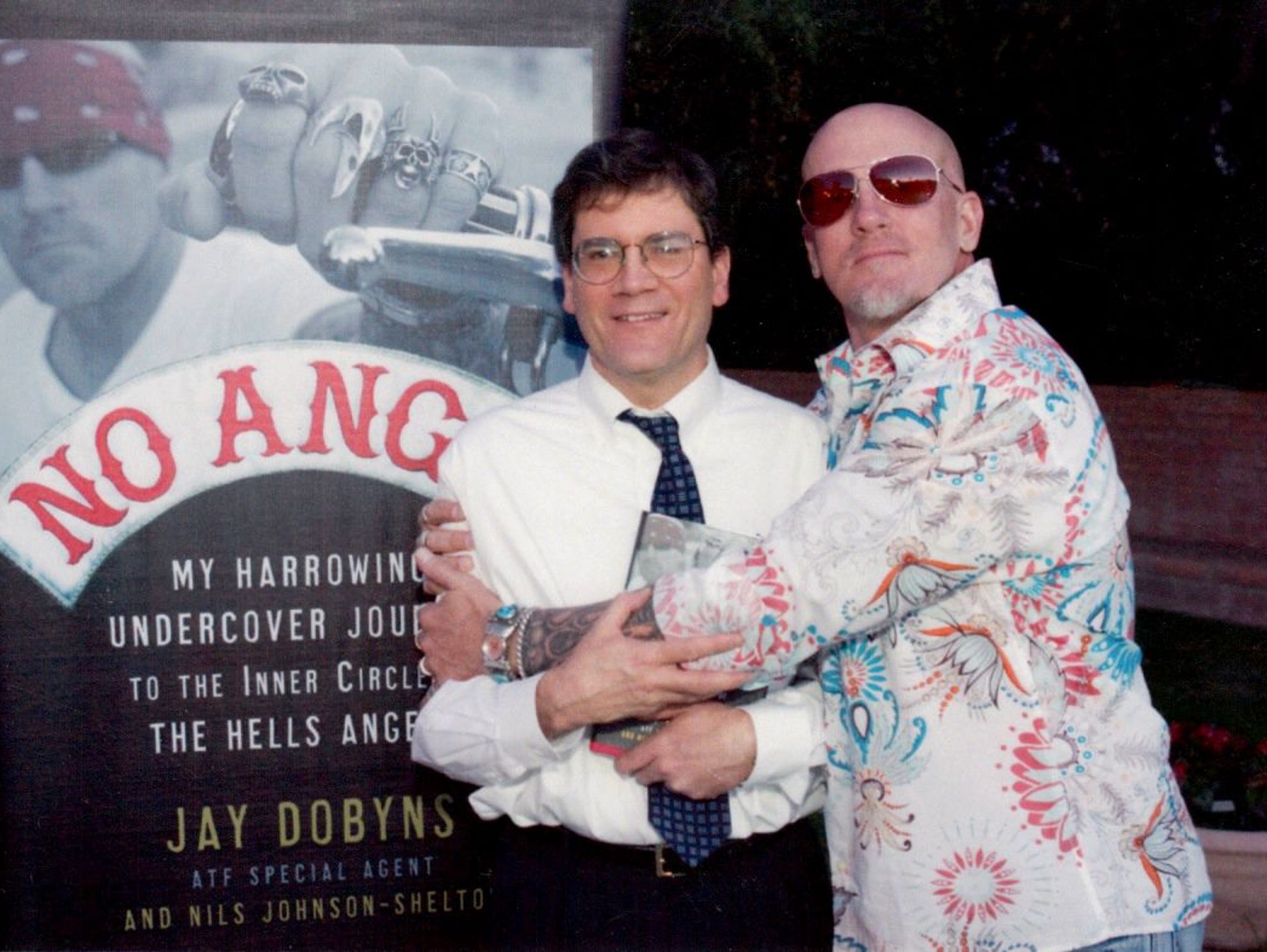

Jim Reed and Jay Dobyns at a backyard celebration of the 2009 release of Dobyns' book, "No Angel."

Jim Reed and Jay Dobyns at a backyard celebration of the 2009 release of Dobyns' book, "No Angel."

(Photo: Timon Harper)

Dobyns came back to Reed.

Reed gave him an honest answer: He had never sued the federal government and didn’t know much about the Court of Federal Claims where it would be filed. But, he vowed to Dobyns, he would learn on the fly and work as hard as he could.

Dobyns sensed that Reed not only believed him, but more, he sensed the desire in Reed to fight an injustice.

“It was that first profound view of that overwhelming sense of fair play,” he said.

Reed would frame the case as a simple contract dispute. He would argue that the government had agreed to keep Dobyns safe and it failed to hold up its end of the bargain.

In October 2008, the paperwork was filed for a case named Dobyns vs. the United States.

Then the work began.

A man in a suitDobyns gave Reed a stack of documents, results of records requests he had filed.

Reed said he eyed the documents with the mindset that Dobyns was wronged. He had to look at them that way, he said, not giving the government the benefit of the doubt. Otherwise, he might miss something.

Reed pored through the documents after his normal workday, after working on cases for paying clients. He worked in the early evening, often camping out at a restaurant, La Grande Orange, near his office.

Periodically, especially as the case got closer to trial, Reed would leave the restaurant at closing time and head back to his office and work into the wee hours. Then, he would drive home for a few hours’ rest before morning.

Reed said he comes from a family of marathon runners. He figures that is where he gets his stamina. He claims to not need much sleep.

It was on one of those pre-dawn drives home that Reed’s overactive brain fixated on something other than law. He gravitated to what his family had used his whole life to deal with stress: humor. Reed started thinking of jokes. Bad one-liner jokes. ... Told by a nightclub comedian. ... Who also happened to be a rabbit.

Reed had already written some rabbit-centric material. His mother had been ailing during her final years and to cheer her up one Easter, Reed dressed as a bunny and made wisecracks at the brunch table: “I love eggs, but I’ve delivered a few too many of these. How about some ham?”

Jim Reed has always used humor to deal with stress. That partly explains why, during preparation of the case, he created a character named Shifty the Rabbit, a nightclub comic.

Jim Reed has always used humor to deal with stress. That partly explains why, during preparation of the case, he created a character named Shifty the Rabbit, a nightclub comic.

(Photo: Photo courtesy of Jim Reed)

Reed named his character Shifty the Rabbit. And, when he needed a mental break from the Dobyns matter, he would think of jokes for Shifty. They would come from the “Take my wife ... please,” vein of humor but be told through the perspective of a cigar-chomping bunny, who knew a little bit about the law.

“I’ve had so many paternity suits,” went one joke, “I leave lettuce out for the process server.”

In his mind, Reed would imagine punctuating these and other jokes with a loud, “Oh.”

Not that he would ever tell these jokes, in character, in public. At least not right away.

That wouldn’t happen until the evening of Halloween of 2009. Reed put on his rabbit suit, complete with a floppy-eared head covering, donned sunglasses and stood near the coffee machines at La Grande Orange.

He told about five minutes worth of jokes, pausing for laughter that never came.

During e-mails back and forth with Dobyns, Reed would sometimes include some Shifty material. Dobyns wasn’t a fan. “Too vaudeville,” he said.

Dobyns tried contributing some Shifty jokes of his own. But Reed said they were just recycled dirty jokes with a rabbit substituted in as the main character.

'Those dudes have no idea what's coming'In March 2010, Reed was in the frozen food aisle of Safeway when his cellphone rang. It was the lead attorney from the Department of Justice.

Dobyns and Reed in 2011.

Dobyns and Reed in 2011.

During the half-hour phone call, the attorney said the government was just as interested as Reed was in finding out the truth. If agents acted wrongly, he vowed, the government wanted to know.

“In my naivete,” Reed said, “I believed that.”

That changed during depositions in the case, which began that summer.

During one, held at Reed’s law office, he grew frustrated. The witness, a former assistant special agent in charge of the Phoenix ATF bureau, George Gillett, gave what Reed thought were deceptive answers. And the government attorneys kept telling Gillett not to answer Reed’s questions.

“Outside, now,” Reed told the attorneys.

In his firm’s lobby, Reed started yelling at the three government attorneys, demanding they let him do his job. The lead attorney turned to walk away and Reed shouted, “Don’t you turn your back on me.” Dobyns grabbed Reed by the shoulders and led him to an outside balcony.

“I was livid,” Reed said. He kicked the metal railing, a move that would leave his ankle smarting for months.

But, for Reed, the exchange solidified what the case was about. His faith in the government’s pursuit of truth eroded. He saw this as a battle against an opponent that wanted to win at all costs.

During the next line of questioning, Reed produced what he saw as a smoking-gun document. Dobyns had found it buried in a stack of e-mails.

In the e-mail, Gillett wrote that he could keep the continuing investigation of Dobyns a secret. He wrote that he knew “how to hide the ball with the best of them.”

Reed started reading the e-mail out loud line by line, asking the agent what he meant. “I can hide the ball with the best of them,” Reed said, according to a tape of the deposition. His voice dripped with contempt. “And what ball were you going to hide?”

Reed said he glanced at the government’s attorney. “The lead attorney just turned white,” Reed said.

Reed expected the government to offer a settlement. In the depositions, he was showing that Dobyns’ story about retaliation seemed plausible.

Testimony looked bad for the government. It showed agents had conflicting stories about the reasons for the tepid response to the original arson call. It showed there was a continued investigation of Dobyns, including tapings of two phone calls. And that documents produced by that investigation were being held out of the ATF system and instead squirreled away in a file cabinet at a nearby Air Force base.

Still, Reed said, the government did not seem to want to settle.

Reed sensed that part of the government’s strategy was to overwhelm and intimidate him. Reed sensed he was seen as “this rube from Arizona” and not as someone who had taken on the government before and won.

Reed thought he saw something else from the attorneys. It was that look he had grown used to seeing ever since he was a little kid on crutches. It was a look he still got when people saw him walk with a hitch that varied based on how his knee was acting that day. It was a look that made him sense people didn’t expect much from him. It was a look that made him want to prove them wrong.

Reed had long ago accepted that life was unfair. That some children are born with crippling diseases and others are not. It was the injustices caused by humans, acting willfully or out of neglect, that angered him.

Reed knew he couldn’t overwhelm or intimidate the government attorneys. But he could outwork them.

Reed made himself known to his adversaries at the Department of Justice, sending persistent and demanding e-mails. The time stamps showed his work habits: 6:48 p.m., 11:48 p.m., 12:17 a.m., 2:26 a.m.

One reply from the DOJ seemed to complain about the constant volley. “You, nevertheless, continue to pepper me with e-mails about perceived issues,” wrote David Harrington, the lead attorney in the case. He noted, in his reply to Reed, that the e-mails were “often lengthy.”

Harrington, through a spokesperson at the DOJ, declined to be interviewed. A spokesperson for the ATF also declined to comment on the case.

As they prepared for trial, Dobyns saw Reed steel himself for the grueling days. During a week of depositions in D.C., a box was delivered to the law firm that was letting Reed borrow some office space. It was Reed’s blood infusion. He prepared an injection while continuing to read documents, as casually, Dobyns said, as if he were stirring a cup of coffee.

“This guy’s going to war on my behalf,” Dobyns said, looking back at the scene. “He’s receiving blood to pump in his body so he could be strong and on his game for me and my family.”

Former federal agent Jay Dobyns, left, with his attorney Jim Reed at his office in Phoenix on Friday, July 31, 2015.

Former federal agent Jay Dobyns, left, with his attorney Jim Reed at his office in Phoenix on Friday, July 31, 2015.

(Photo: Michael Schennum/The Republic)

The day the trial began in Tucson, Dobyns visited Reed in his hotel room. He saw him wrapping elastic bandages tight around his ankles and knees. Reed told Dobyns that since he was going to be on his feet for much of the day, he needed to keep the swelling out of his joints.

Watching Reed wrap his legs before court, Dobyns said he thought of a warrior preparing for battle. “Those dudes have no idea what’s coming,” Dobyns remembered thinking: Reed was “the baddest ... on the planet.”

The two prayed before the trial. Dobyns said he didn’t ask God to help him win, but rather to give Reed wisdom. “Help him be clever,” Dobyns said, recalling the prayer. “Help him be strong. Help him serve whatever your goal is for today.”

The judge scheduled the trial for three parts in 2013. The first two weeks would be in Tucson in June, then move to D.C. for a third week in July. There would be a months-long break before closing arguments would be held in Tucson in February 2014.

Reed had an effective, if exhaustive, trial strategy. Based on the depositions, Reed expected that several witnesses would change their stories at trial.

He and his paralegal, Jeffrey Elder, went through transcripts looking for pivotal answers. Elder than created video clips of those key lines of testimony. Each was bar coded so it could be called up quickly at trial.

If witnesses would change their testimony, Reed would be ready to catch them.

In court, Reed used the clips for what is legally called impeachment of a witness. After an answer that differed from the deposition, Reed would ask the judge, “May I impeach, your honor?” If given the approval, he would wave a laser wand over a bar code and a video clip would play.

Dobyns said it appeared to him the judge grew weary of this; not necessarily the video clips, but that there were so many changing stories.

At times, Reed said, the wand would become Pavlovian. If he held the wand up, a witnesses would stop and say they wanted to give a different answer.

By the time of closing arguments in Tucson, it appeared Judge Francis Allegra had deep concerns about the government’s actions.

“I don’t think there’s serious question that certain agents of the ATF here acted inappropriately, likely contrary to Agency policy and maybe even unlawfully in dealing with Agent Dobyns,” he said in court before arguments began, according to a transcript.

Allegra said it appeared the agents’ bad conduct was motivated “by professional jealousy, intra-agency rivalries within the ATF or perhaps just spite ...” Allegra also said he was convinced that some ATF agents had been “less than candid” in his court. “I will get to the bottom of who is telling the truth here,” Allegra said from the bench.

The judge’s ruling would come in August 2014.

Dobyns was driving home when Reed reached him with the news.

Reed told him he had won the case, but that he probably wouldn’t be happy with the dollar amount he was given. The judge said Dobyns was owed $173,000 in compensation, not the millions originally requested in the lawsuit. “Praise God,” Dobyns said.

A victory and a defeatAt home, on his computer, Dobyns read the ruling for himself.

Reed and Dobyns in October 2015.

Reed and Dobyns in October 2015.

Judge Allegra said the government committed a “gross breach” of its contract with Dobyns. The judge also described two ATF agents’ testimony in ways that read like a thesaurus entry for lying: “unworthy of belief,” “remarkable tapestry of fiction,” “lack of candor,” “incredible testimony,” “thoroughly unbelievable” and “lacked credibility.”

Allegra also said it appeared that a government attorney tried pressuring two witnesses, ATF agents who years later had tried to reopen the arson investigation. The attorney, according to the judge’s ruling, told the agents that reopening that investigation would damage the government’s case against Dobyns.

The judge ordered that his ruling be sent to the Attorney General’s Office and two oversight agencies and that attention be called to the paragraph where he described that threat.

Allegra would also file an edict that said seven government attorneys — their names were redacted from the document — could no longer file briefs or appear in court for this case.

It wasn’t over. After Allegra issued his ruling, another witness told the judge he had received threats after giving testimony favorable to Dobyns. In December, Judge Allegra asked for an appeals court to give the case back to him so he could hire an investigator to look into whether government attorneys had committed fraud on the court.

That investigator ruled in July that the behind-the-scenes action did not affect the judge’s verdict. That any intimidated witnesses testified anyway and that the judge saw through any deception.

Allegra, the author of the ruling, died of a brain tumor this August. Reed said he didn’t know about the judge’s health issues, but felt humbled knowing Allegra worked on this case in his final months.

The matter is now in the hands of the chief judge of the Court of Federal Claims, Patricia Campbell-Smith. She took final briefings on the matter in September.

For Reed, the judge’s original ruling was a vindication. It showed he was right to believe Dobyns.

But he lost his belief in something else.

Reed has become wary of federal agents, having seen what they did to one of their own.

This year, Reed started noting vehicles following him. He started posting about it on Twitter. “Hey I’m taking a break from work for a few minutes guys. Start your engines. Here I come,” he wrote in March.

In a court filing, Reed said a retired ATF agent, after hearing his stories, told him his suspicious were correct: He was being followed. In the filing, Reed also avowed that the agent himself reported being photographed and followed after leaving Reed’s law office. Reed asked the court to consider holding a hearing where the government could explain why it felt the need to surveil him.

Reed continued to vent his frustration through Twitter. This was from April: “... when you tail a detail-oriented lawyer who just beat DOJ w/ an undercover agent-client, you’re as stupid as they come.”

On Easter night, around 10 p.m., Dobyns was at his home in a remote part of the Tucson metro area. His children and wife were asleep. Dobyns heard a knock at his door.

“People don’t knock on the door at my house,” Dobyns said. He grabbed his gun and held it by his hip.

He opened the door and saw his attorney. Standing on his stoop. Wearing sunglasses and a rabbit suit.

Reed had spent the holiday with his family and decided that Shifty the Rabbit should pay a surprise visit to Dobyns. After all, Dobyns’ wife liked the bunny jokes.

Dobyns relaxed his hand on the gun.

Reed stood over Dobyns’ sleeping wife, Gwen. “Easter’s not over,” he yelled.

All gathered in the living room for a performance.

“Don’t pull my leg,” Reed said as Shifty. “My left rear paw is already hanging from some guy’s key chain. I tell ya, one guy’s luck is another bunny’s prosthetic.”

As Reed drove the two hours back to Phoenix, his Shifty costume in the back seat, his blood boiled at the thought of being followed by the FBI. That this was his reward for beating the government. He formulated a silent act of defiance.

He pulled into his driveway, went inside and changed, grabbed a bottle of club soda and sat on a chair on his porch.

If an agent were watching him, he thought, the log of the evening would have to include a line that went something like this: Individual sat outside, occasionally drinking from a bottle of Perrier, all the time wearing a bunny suit.

Richard Ruelas writes about the unique people of Arizona. Read more from him here and at bestreads.azcentral.com.

http://www.azcentral.com/story/news/local/best-reads/2015/10/17/jay-dobyns-atf-hells-angels-attorney-jim-reed/74015938/

http://www.azcentral.com/story/news/local/best-reads/2015/10/17/jay-dobyns-atf-hells-angels-attorney-jim-reed/74015938/

Similar Threads

-

I fought for you

By kathyet2 in forum Other Topics News and IssuesReplies: 0Last Post: 01-22-2014, 04:39 PM -

Former Hells Angels leader slams New York beating after motorcycle chase

By JohnDoe2 in forum General DiscussionReplies: 1Last Post: 10-05-2013, 07:50 PM -

We fought for you!!

By SOSADFORUS in forum Videos about Illegal Immigration, refugee programs, globalism, & socialismReplies: 6Last Post: 09-29-2010, 02:11 PM -

Drug smuggler linked to Hells Angels sentenced to 14 years

By JohnDoe2 in forum illegal immigration News Stories & ReportsReplies: 0Last Post: 07-27-2010, 04:13 PM -

Immigrant 'underclass' fought

By Brian503a in forum illegal immigration News Stories & ReportsReplies: 1Last Post: 03-23-2006, 05:59 AM

LinkBack URL

LinkBack URL About LinkBacks

About LinkBacks

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Listen to William Gheen on Rense Apr 24, 2024 talking Invasion...

04-25-2024, 02:03 PM in ALIPAC In The News