Results 1 to 4 of 4

Thread: The India Bush Didn't See

Thread Information

Users Browsing this Thread

There are currently 1 users browsing this thread. (0 members and 1 guests)

-

03-05-2006, 01:16 PM #1

The India Bush Didn't See

http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.c ... CS7C20.DTL

Will Bush's 'Globalization Policy' help create America into another 3rd World Country?

Will Bush's 'Globalization Policy' help create America into another 3rd World Country?

The India Bush didn't see

The nation's liberated economy -- portrayed by globalization forces as an antidote to poverty -- has done little for nearly 300,000 poor people, the most of any country

Mike McPhate

Sunday, March 5, 2006

New Delhi -- Among India's poor, survival is still won by acts of despair and cunning. It's a daily quest whose reward is a plate of rice or a simple medication.

Farmers in Maharasthra hang banners offering their kidneys for sale; overworked medics in Gorakhpur fashion tubes from paper to deliver oxygen to the diseased; hungry parents in the barren fields of Orissa sell their children for the price of a bag of grain.

Millions roam the country in pursuit of work, trading the want of the village for the indignity of bonded labor. At outdoor kilns dotting the scorched terrain of Andhra Pradesh, parents and children toil side by side mixing and molding bricks from dawn till midnight. By doing this, a family of six earns about $5.50 per week, enough for one evening meal of unripe tomatoes and broken rice, reject kernels used normally as chicken feed.

The workers bathe in the stagnant mud pits used to mix the bricks and sleep in mattress-size hovels no taller than a man's belly button, which contain their entire estate: some tattered clothes, a hand broom, a few dinged-up pots.

"We were born in the mud, we've spent our lives in the mud, and we'll die in the mud," says Bansi Dhar Bag, 43, his skin blackened by a lifetime of kiln work. "We have to lead our lives like this. We suffer a lot, but we have to survive. We have to suffer."

Such is the burden of poverty for more than a quarter of India's 1.1 billion people. It's the nation with the largest number of poor people in the world. Although their ragged slums cram the roadsides and river banks of capital New Delhi, they almost certainly did not cross the gaze of President Bush, who arrived here Wednesday for a two-day visit during his first trip to India.

India has sought to portray a very different image to the outside world, one of a global leader. In conjunction with Bush's trip, the United States gave a nod of approval to that aim, inking a nuclear energy agreement that effectively normalizes India's furtive nuclear status. Many feel that a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council is inevitable.

India's rise to prominence began with domestic market reforms in 1991 that broke the dam of globalization and sent the country's economy soaring -- growing at an average of 6.8 percent since 1994. In just a decade, the land of lepers and snake charmers was supplanted by one of tech tycoons and MTV veejays.

Contrary to government claims however, the liberated economy -- commonly portrayed as an antidote to poverty among global financial institutions -- has done little for India's poor, say several leading economists, including Jean Dreze, Martin Ravallion and Raghbendra Jha. The most notable outcome of reforms, they say, has been to make inequality and even wider chasm.

As the number of Indian millionaires grew an estimated seven-fold during the 1990s, the number of hungry Indians actually rose, according to the United Nations' Food and Agricultural Organization.

Decades of underinvestment in human development in India, concluded the United Nations in its 2005 human development report, have yielded a grim set of statistics: half of all children remain malnourished, half of women remain illiterate, more than 80 percent of the countryside lacks access to a telephone or a toilet.

There's been a "tremendous lack of responsiveness to the needs and aspirations of the underprivileged," wrote Dreze in the journal Economic and Political Weekly. "Endemic hunger has been passively tolerated, and is barely noticed in public debates and democratic politics."

Soon after the Congress Party's coalition won parliament in 2004 -- an upset victory credited to unrest among rural voters -- it named the "battle against poverty" its top priority. The party's most ambitious strategy came last month, a job guarantee program that allots the poorest villagers with 100 days per year of crew work on rural infrastructure projects.

Among the scheme's targets is Mittadoddy, a red dirt village of 120 thatched homes about 100 miles south of the high-tech city of Hyderabad in southern India. In this part of the country, about 3,000 farmers, hounded by unrelenting drought and ruinous debt, have committed suicide since 1998; local newspapers have reported dozens of starvation deaths.

A group of Mittadoddy villagers gathered one afternoon beneath a few browning palm trees. Like many of India's poor, they are untouchables, bottom-dwellers of Hinduism's waning system of caste. Their fingers and toes are like hard leather from decades of manual labor; they use ash for soap, walk a mile for drinking water, and habitually go to sleep hungry, they say. Only 1 in 5 can read, says a local official.

The villagers describe how shocks such as crop failure, illness and widowhood drive lives of subsistence to ruin.

Ill-timed rainfall forced Esaku Juttu, 52, to abandon his 2-acre crop of ground nut and take a job lugging bricks for 90 cents per day, a pittance against the $890 he borrowed to dig a tube well. He's put five of his seven kids to work in nearby cotton fields. "If I sent them to school we wouldn't survive," he says.

Ten-year-old Shubamani Ovadagiri, a deaf girl in a green dress, had to have an infected appendix removed just weeks ago, an operation that doubled her family's debt to $450. "I have nothing left to give my child," says her mother, Deepama Ovadagiri. "We have no food, no milk, no vegetables."

Few in India trust the administration's promise of employment, skepticism buttressed by a 2004 World Bank study which found that India's anti-poverty schemes commonly get misappropriated and end up "serving the wealthy and powerful far better than the poor."

"Political leaders come to power with huge agendas and promises to the people," says Vadagini Tippamma, 40, a woman in a black floral sari. "But they never fulfill their promises. They never show their faces again."

About half of the surrounding district's residents have fled in search of work, most for the city -- going "from frying pan to frying pan" as one activist put it -- where wages can double to $2 or $3 per day, but the living is cramped and squalid.

The tide of such migrants has bloated urban India: Since 1991, the number of cities with more than a million people has grown from 23 to at least 35. Most pitiful are millions of stray children, in flight from poverty-stricken or abusive homes; their journey leads inevitably to the nearest train platform and a new family of pickpockets, heroin addicts and pimps.

The capital's railway children hang out at a dusty park -- haunted, they say, by a headless ghost -- across from Old Delhi Railway Station. One chilly morning, several boys play with bricks and a broken seesaw, others hover over a few burning newspapers. Their faces and clothes are engraved with grime, and most have bruises, cuts, or rashes -- "our first priority is just to make them well physically," says one aid worker.

Ajay, 10, calls his mother a "whore'' who beat him with a stick; Ali, 13, says his parents died of tuberculosis; Hitesh, 11, says his father threw him out after his mother died.

The boys earn a living now by begging, collecting bottles or stealing. Ajay, who wears adult-size tennis shoes that force him to take big, clumsy steps, says hunger always lurks. "It's not as if we earn daily," he says. "We earn 30 rupees one day" -- about 68 cents -- "and nothing the next."

"Big kids beat us and take our money," adds Ali, a round-faced boy with stick limbs. "Cops beat us, too."

The boys have grown hard with their years of vagrancy, swaggering among the tracks like little thugs and raising fists at the slightest provocation. Most railway children are addicted to glue or paint thinner, and some carry razors for pick-pocketing and fighting.

Beneath tough skins, though, they are still boys, and quick with tears in a fight or a jogged memory of home. With glazed eyes, Hitesh sucks paint thinner from a dirty blue rag and sobs as he tells how his father rejected him. "My mom died while I was sleeping," he says. "I don't know why, but he blamed me."

Devika Singh, a founder of Mobile Crèches, a charity that sets up shelters for migrant children, says India's wayward kids reflect a country that is simply apathetic to the poor.

"I'm not doubting at all that the economy is in much, much better shape," she says. "But what happens to your social issues? Can you really balance your resources? You're free to do what you like, free rein, no control, employ, hire, fire, take, give back. But how much can you really keep for the social net? And how much can you actually deliver?"

The kiln worker Bag views his poverty in starker terms, as a matter of cruel design. Like his father, who died from "the worry of seeing us in pain," he expects lives of misery for his own children, he says.

"If we become rich, then who will work for the rich people?" he asks. "It's the same everywhere. Nothing changes."

Mike McPhate is a freelance writer based in India. Contact us at insight@sfchronicle.com.RIP Butterbean! We miss you and hope you are well in heaven.-- Your ALIPAC friends

Support our FIGHT AGAINST illegal immigration & Amnesty by joining our E-mail Alerts at http://eepurl.com/cktGTn

-

03-05-2006, 02:30 PM #2Senior Member

- Join Date

- Dec 2004

- Location

- Oak Island, North Mexolina

- Posts

- 6,231

"The India Bush didn't see

The nation's liberated economy -- portrayed by globalization forces as an antidote to poverty -- has done little for nearly 300,000 poor people, the most of any country "

Missed some zero's: 300,000,000.Join our efforts to Secure America's Borders and End Illegal Immigration by Joining ALIPAC's E-Mail Alerts network (CLICK HERE)

-

03-05-2006, 02:37 PM #3Banned

- Join Date

- Feb 2006

- Location

- was Georgia - now Arizona

- Posts

- 4,477

That's right. The 300,000 is their 'burdgeoning' middle class. That's 300,000 less jobs for OUR middle class.

-

03-05-2006, 03:27 PM #4

The World's Most Dangerous Places

Hi Butterbean, how ya doin?

Preface: The United States is on the list of the world's most dangerous places.

And, Butterbean, yes I have a copy of Pelton's book and, yes, it kicks ass.

About India, where our jobs are going.

what the Bangalore vendors don't tell their US clients (or anybody else)!

http://www.comebackalive.com/df/dplaces/india/index.htm

List of the world's most dangerous places (list includes Mexico)

http://www.comebackalive.com/df/dplaces.htm

Book review:

Pelton's book contains far more detail than the website.

Highly recommend if you travel or plan to travel anywhere.

http://www.comebackalive.com/

Paperback: 1088 pages

Publisher: HarperResource; 5th Rev edition (April 1, 2003)

Language: English

ISBN: 0060011602

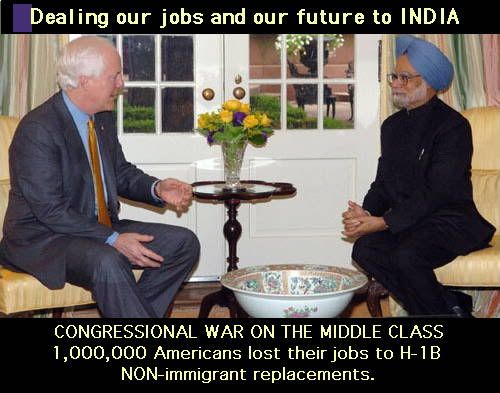

What part of "We don't owe our jobs to India" are you unable to understand, Senator?

LinkBack URL

LinkBack URL About LinkBacks

About LinkBacks

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Illegal Alien Arrested for Stabbing Fellow Illegal to Death at...

04-23-2024, 01:10 PM in illegal immigration News Stories & Reports