Results 1 to 1 of 1

Thread: The Largest Landowner in America

Thread Information

Users Browsing this Thread

There are currently 1 users browsing this thread. (0 members and 1 guests)

-

09-29-2012, 12:24 PM #1

The Largest Landowner in America

Meet the Largest Landowner in America

The media billionaire John Malone now owns 2.2 million acres, putting him ahead of his pal Ted Turner as the nation's No. 1 landlord.

By Jeff Hull | Fortune Ė 16 hours ago

By Jeff Hull | Fortune Ė 16 hours ago

On the Colorado High Plains, John Malone sits in a generous -- but not grandiose -- corner office on the second floor of a blocky, granite-faced building in a nondescript corporate park in Englewood. If, in real estate, location is everything, it's curious that the largest private landowner in America chose an office location, an hour from downtown Denver, that ... well, it isn't much. Not much to look at, anyway.

But the building and its location are Malone writ large: standalone, brawny, and commanding views of clean sky and snowcapped mountains shining like chrome in the distance. Malone, 71, whose thick hair is as white and flawless as his wrinkle-free shirt, sits behind his desk wearing an elegant rose-colored tie and tells a visitor, "My wife and I are going to look at something that's for sale on Friday."

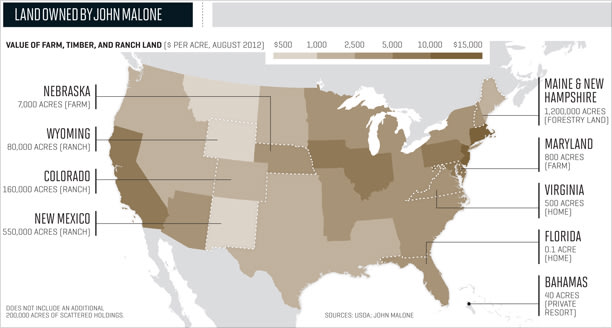

By "something" Malone means land. Given that in 2011 Malone bought 1.2 million acres of Maine woodlands, thereby surpassing his old friend Ted Turner as the nation's largest private landowner, one might view the Friday shopping trip as a touch superfluous. Malone doesn't. He's got the land bug, thanks in part to Turner, now the second-largest private landowner in America, with whom he has a fond rivalry. If, as the German philosopher G.W.F. Hegel posited, "property is the first embodiment of freedom," Malone is one liberated individual. According to The Land Report magazine, he now owns an estimated 2.2 million acres of U.S. cropland, ranch land, and woodland, an area about three times the size of Rhode Island. (The largest landowner in the world is Queen Elizabeth II, because technically she owns places like Australia and Canada.)

There's no master plan to the way Malone acquires land, no imperialistic imperative, no mano a mano contest with Turner -- "We are not having a race," Malone says. "I certainly applaud what he's done, and we share very common goals" -- but neither is there any indication that he will stop anytime soon.

Although Malone expresses manifold motivations for buying more land, the primary reason seems to be simply that he can. "Basically, for my whole life all my assets have been tied up in the companies I've started and run," says Malone, the founder and chairman of Liberty Media (LMCA), a major distributor of TV entertainment, sports, and other programming, including Discovery Channel, USA, QVC, Encore, and Starz. In recent years he has successfully spun off businesses and is now free, he says, to spend more of his wealth on land, although it's not clear how much he has invested so far in his holdings. But he can afford it. After years of wheeling and dealing, Malone is worth an estimated $5 billion.

No matter where he is or whom he's with, John Malone seems at home. Jerry Lindauer, an early player in the cable-television industry, once said of Malone, "You could put him on a panel of nothing but experts in their respective fields, be it financing, marketing, programming, engineering, technology, whatever it is ... he was a tour de force. He can cross all disciplines."

One particular instance of Malone's savvy was understanding that the cable-TV business was what is now called a "content business" long before most people had any idea that such a thing existed. He was also good at engineering complex financial transactions in the field of telecommunications. Entering a business deal with Malone is like playing chess with a grand master -- not only are you going to lose, but it's going to take years for you to figure out just how early and thoroughly you were outmaneuvered. Malone has crossed fountain pens with the greatest media titans of the telecommunications age -- Ted Turner, Rupert Murdoch, Barry Diller -- and often walked away richer.

Essentially, after a mind-numbing series of mergers and stock splits, spinoffs and standoffs, Malone emerged on the sunny side of some of the biggest business deals in the history of telecommunications. At one point or another, he has owned stakes in Sprint (S), Interactive Corp., Motorola (MSI), Time Warner (TWX), News Corp. (NWSA), AT&T (T), Sirius XM (SIRI), and even analog media like Barnes & Noble (BKS). The media titan never shied away from a fight. In a 1994 Wired interview, Malone joked that Reed Hundt, then chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, should be shot. Not exactly Mr. Nice Guy.

Malone didn't know how much he liked land until he came West as a relatively young man. Raised in Milford, Conn. -- then a village of 2,500 people -- Malone spent summers on his father's family's farm in southeast Pennsylvania. After graduating from Yale in 1963 and earning a Ph.D. in operations research from Johns Hopkins, Malone by 1970 was running a division of General Instrument Corp., a pioneer in the cable-TV industry. Dissatisfied with the company's management and told he was too young to run the place himself, Malone in 1973 moved to Denver and took a 50% pay cut. There he worked with a customer he always admired, an entrepreneur named Bob Magness who ran a fledgling -- and nearly bankrupt -- cable-television company called Tele-Communications Inc. Malone would build TCI into what would become the second-largest cable-TV company in the country, after Time Warner.

Magness, a former cattle rancher and seed salesman, was "really as much a father and a mentor as a partner," says Malone. They had adjacent offices. They shared motel rooms when they traveled "because we were cheap," he recalls. Malone remembers his 25 years of working with Magness with great fondness, and his mentor's enthusiasms had a way of rubbing off on Malone -- including a longing for land.

"Bob Magness was absolutely in love with land and with ranches in particular, and that really introduced me to the possibility of owning landscape-size pieces of land," Malone says. "In the early '80s we bought a piece of land on behalf of the company and put together the [80,000 acre] Silver Spur ranch in Saratoga, Wyoming."

Magness died in 1997, and two years later Malone sold TCI to AT&T for $48 billion -- the second-largest business transaction in the country up to that time. (Malone would later spin off Liberty Media and leave AT&T with it.)

That same year, Malone bought the Silver Spur, his first major land purchase, from TCI. "I knew the ranch and loved it," Malone wrote in a recent e-mail. Following that acquisition he went on a land-buying orgy in Wyoming and Colorado. "I liked the efficiency of scale and learning about the ranching business," he recalls.

But it wasn't until he toured some of Ted Turner's landholdings that Malone began to see an even bigger picture. "Ted and I have been buddies for many, many years, and in many ways the idea of investing in land ownership and stewardship came to me from Ted. He was the one who gave me the concept that you could do well and do good in landownership." Fortune.com

Fortune.com

For his part, Turner is proud of anything he might have sparked in Malone. "John feels a deep reverence for the land and is very aware of the responsibilities that come with being a landowner. I also feel that way. We both see landownership as a personal investment, but also an opportunity to contribute to the well-being of our planet and its inhabitants," Turner wrote in an e-mail.

John Malone is many things -- a telecommunications mogul, a cross-country skier, a multibillionaire, a family man, a yachtsman, an unreconstructed and sharp-tongued libertarian -- but he is, first and foremost, convincing. His voice, substantial and steel-cored, helps ensure that when you hear Malone speak, you believe what he's saying. Also, you know that by the time the sentence slices into the air, Malone has thought about what he's saying, possibly for years. Despite, for instance, his mentioning of "aesthetics" first on the checklist he considers before acquiring a new piece of property, you know he isn't suggesting he's amassed 2.2 million acres of "pretty."

After asking himself if a particular parcel of land is something that deserves to be preserved from an aesthetic point of view, from a biodiversity point of view, from an if-we-don't-preserve-it-what's-going-to happen-to-it point of view, Malone eyeballs issues closer to the bottom line, which provokes a spreadsheet of questions:

Does it make economic sense? Does it bleed money or is it self-supporting and self-managing? Do I have to get involved in day-to-day operations of the business, or does it have competent current management? Does it represent economic diversification for myself and my family?

"Productive land is one of the very few permanent values throughout history," Malone says. Others are certainly acting on that assumption. In the Midwest, farmland prices have skyrocketed. From 2011 to 2012, according to the Chicago district office of the Federal Reserve, Iowa farmland prices saw a 27% increase. Last year a farm in Iowa's Sioux County sold for a record $20,000 an acre. On Canada's plains, investment funds are buying up wheat and barley farms in Saskatchewan. Over the past decade farmland has generated annualized returns of 13.9%.

Even less lucrative ranch land has become highly coveted. Jim Taylor, recently retired as the managing director of Hall & Hall, one of the country's largest ranch-land brokers and managers, says that despite economic hardships in residential real estate, ranch land has been a solid investment. Hall & Hall recently had its best run in the company's 70-year history. From the last quarter of 2010 through 2011, the brokerage sold about $460 million worth of ranch land.

"The buyers are people with a very large net worth who don't need a lot of cash return," Taylor says. "I think these purchasers are worried about inflation, and they're willing to accept an investment that doesn't get you a great return. You put a certain amount of value in land today and you come back a thousand years from now, it's still going to have value -- whether you're measuring it in dollars or rubies or rubles."

Taylor, who attended Yale but didn't know Malone, has been watching Malone's acquisitions with interest. "When there's any kind of uncertainty in the national or international economy, everybody sits on their money," Taylor says. "You don't invest in long-term assets when the world may be coming apart. On the other hand, if you're really smart and really rich, that's when you do invest in long-term assets because that's when everybody is trying to get rid of them. That's where I think Malone fits into it."

Malone wants his land to generate at least enough revenue to support itself. He playfully chides his conservationist friend Ted Turner for trying to "take [his land] back to precolonial times, where I'm content to take it back to perhaps the late 1800s."

One thing he looks for is synergy. Malone's cattle ranches in Wyoming, New Mexico, and Colorado send cows to his Nebraska feedlot to fatten on grain from farmland he also owns in that state, boosting productivity and generating a little revenue. But there are so many ways for billionaires to generate revenue.

"People say to me, 'Why don't you own a bunch of gold because of how you feel about the government?'" says Malone, a libertarian who is not enamored of the federal government's handling of debt or, really, the federal government as whole. "But I have a really hard time owning assets that aren't productive."

Malone figures that his cropland will get a 5% operating return as an investment, while his forest investments in New Hampshire and Maine should get closer to a 2% to 3% real return. Ranching, he says, gets close to zero in terms of an operating return. But it does have potential for appreciation, especially in times of inflation.

"In the long view in real dollars," contends Malone, "cropland is probably best, because it's producing a commodity that is consumed by a world market." One thing Malone likes is that the demand for farm and wood products (and, to a lesser extent, beef from ranching) is independent of domestic fiscal and monetary policies. "You're not dealing in strictly the local currency," explains Malone, "so you get protection from the fact that the thing your asset produces is desired by a worldwide market. To me it looks like one of the safest places you can invest money is productive land."

When negotiating land purchases, Malone calls upon the same skills that served him so well in the business world. Eric O'Keefe, editor of The Land Report, a publication dedicated to monitoring the high-end land market, says, "John Malone is as tough in his timber dealings and is as disciplined in his ranch acquisitions as he is in any transactions made on the Street." The 290,000-acre Bell Ranch -- about 453 square miles of New Mexico -- was originally listed for $110 million in 2006, then dropped to $85 million in 2010, when Malone entered the picture. Malone is believed to have paid between $60 million and $65 million for the ranch. "He's very open-minded and thoughtful about the process it takes for a seller to sell," says Ron Morris of the Colorado-based Ranch Marketing Associates, who has represented Malone in several large Western land deals. "But John's not foolish. In my experience with him, there's no second chance. He'll make one offer and moves on."

And yet, one look at Malone's history with land and it's easy to see that all this land-grabbing isn't only -- or perhaps even mostly -- about investment. Malone and his family are active outdoors enthusiasts. As a kid, Malone says, he could "go down to the water and get in a boat and lose yourself pretty quickly." On his vast holdings in the Northeast he likes to snowmobile -- particularly on the long stretch he owns along the border with Canada. He pursues less mechanized activities too: cross-country skiing in the north woods, fly-casting from a sea kayak along the mangrove flats on his private island in the Bahamas.

And so, lying beneath the financial spreadsheets and income forecasts, there's a romance to owning all these places. It seeps through when Malone suggests he might covet land because he's of Irish ancestry. "I actually do believe," he says, "that there may be a genetic element in wanting to own the land you're on. For 400 years the Irish farmed land that was owned by English landlords. The farmer's existence was temporary, transitional. I'm not a believer in mystical things, but I am a believer in evolution, and there could well be some element of generational memory that goes into this kind of stuff. Or at least a way of thought. Call it an empathy."

When the conversation turns to conservation, Malone starts to sound like an MFA student in creative writing. "The point is, going out on one of these ranches and being able to look for miles in any direction and seeing pretty much the way it used to be, and knowing you can go back in 10 years and it will look pretty much the same way -- it's a value, an aesthetic. You defend it on the basis that you're doing this on behalf of your fellow man."

Which for this shrewd businessman is, of course, only part of the story.

Meet the Largest Landowner in America - Yahoo! FinanceNO AMNESTY

Don't reward the criminal actions of millions of illegal aliens by giving them citizenship.

Sign in and post comments here.

Please support our fight against illegal immigration by joining ALIPAC's email alerts here https://eepurl.com/cktGTn

LinkBack URL

LinkBack URL About LinkBacks

About LinkBacks

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

We must push through early Thurs at this critical moment

04-24-2024, 10:44 PM in illegal immigration Announcements