Results 1 to 1 of 1

Thread Information

Users Browsing this Thread

There are currently 1 users browsing this thread. (0 members and 1 guests)

-

08-25-2010, 08:58 PM #1Senior Member

- Join Date

- May 2007

- Location

- South West Florida (Behind friendly lines but still in Occupied Territory)

- Posts

- 117,696

"Contained Depression" We Are In Deflation Here an

Wednesday, August 25, 2010

"Contained Depression"

Kevin Feltes, an economist for the Jerome Levy Forecasting Center, solicited my opinion on a couple of their recent articles.

Levy comes down on the side of deflation, as do I. However, the devil is in the details, as always. I will go through one of their articles in a point-by-point fashion, stating where I agree and disagree with their analysis.

This is a long post. Please give it some time.

Please consider Widespread Fear of the Wrong Kind of Price Instability. http://tinyurl.com/28uqqhp

Levy:

It is not inflation but more disinflation and ultimately deflation that lie ahead in the 2010s.

Inflation worries remain a major part of the market backdrop, and the past year has brought new price stability concerns to investors. During that time, we have written about inflation fears, deflation risks, and the relationships between price trends and monetary policy, fiscal policy, Treasury debt levels, foreign debt holdings, and various other issues. We have argued that rising inflation will not be a threat in the coming years and that disinflation and some deflation are the real worries. Our position remains unchanged.

1. Why It Will Be Very Difficult for Inflation to Accelerate in the Next Few Years

The dominant influence on price trends in the near future and for years to come will be the deflationary influence of chronically high unemployment. The economy not only has gone through a deep recession but also has entered a contained depression, a long period of substandard economic performance, chronic financial problems, and generally high unemployment. The contained depression is likely to last about a decade; it will end in the latter half of the 2010s at the earliest and could stretch into the 2020s

In the years ahead, chronic high unemployment will weigh heavily on labor costs; chronic economic weakness will tend to keep profit margins under pressure and firms focused on cost control; and global instability and large areas of depression (contained or otherwise) will reduce upward pressures on prices of imported commodities and are likely to cause these prices to fall much of the time.

Even if imported commodity prices, most notably oil prices, rise sharply at times, they will not have a large, lasting effect on inflation as long as labor costs are decelerating or actually falling.

Labor costs are the dominant inflation influence not only because they are the single biggest component of prices, but also because labor costs are heavily affected by compensation rates, which fuel consumer spending and are therefore tied to the ability of firms to pass on inflationary price increases to consumers.

By contrast, oil prices, which are widely believed to be a critical inflation signal, have a weaker relationship to inflation over time, although they can be an important short-term influence. Labor cost inflation will remain subdued or even negative as long as unemployment remains high, and the prospects for a real recovery in labor markets are poor. A tightening labor marketâa falling unemployment rateâwould at some point trigger inflationary pay increases. Conversely, any unemployment rate that is substantially above such a trigger point indicates excessive competition for jobs and a tendency for pay raises to shrinkâor pay cuts to become larger and more common. The trigger point, which varies from one business cycle to another depending on a variety of circumstances, is by any reasonable estimate far below the present figure of nearly 10%.

Mish Response:

I like the concept of a "contained depression".

We are certainly in a depression. However, 40 million people on food stamps as of August 2010, masks that depression. The cost of the food stamp program is on schedule to exceed $60 billion in fiscal 2010. For comparison purposes, there was just over 11 million on food stamps in 2005.

Please note there are 14.6 million unemployed, but of them 4.5 million of them are receiving regular unemployment benefits and another 4.7 million are receiving extended benefits. Thus 63% of those unemployed are receiving benefits. Being paid while not working also masks the depression.

In addition, there is massive underemployment with 8.5 million working "part time for economic reasons" and another 2.6 million "marginally attached" workers who want a job but are not considered unemployed because they have not looked for 4 weeks. This is "containment" of sorts, as the official numbers mask the depth of the unemployment problem.

Finally, countless millions have not paid their mortgage for months or even a year without being foreclosed on. Free from mortgage expenses but having a place to live certainly makes life a lot easier.

Missing the Boat on Labor-Induced Wage-Price Spirals

I disagree with Levy when it comes to the issue of wage price spirals.

Levy's statement "Labor cost inflation will remain subdued or even negative as long as unemployment remains high" is not true as evidenced by the stagflationary 70's and 80's complete with Nixon's wage-price controls that were dismantled as a failure in 1974.

The following three charts will prove my point.

Unemployment Rate 1960 to Present

CPI 1960 to Present

Annualized Wage Growth 1960 to Present

Clearly there is no consistent relationship between the unemployment rate, the CPI, and wages.

Nonetheless, I believe Levy is correct about labor costs, for different reasons.

My reasons include global wage arbitrage, boomer demographics, and overcapacity in the face of secular changes in consumer psychology (the willingness and ability of consumers to take on more debt.)

Those forces will act as a huge damper on consumer demand for goods and services, a damper on business' ability and desire to expand, and in turn a damper on both wages and prices, regardless of what the Fed tries to do.

The critical factor in that list is consumer psychology - the willingness and ability of consumers to take on more debt.

In the 70's, households went from one wage earner to two, increasing the ability of households to take on debt. Interest rates falling from as high as 18% to where they are today increased the ability of consumers to take on debt. Belief that rising asset prices (especially home prices) would guarantee a nice retirement increased the willingness of consumers to take on debt, and debt they did take on in the form of second mortgages, home equity lines of credit, etc.

Now, it's payback time for a global credit boom of epic proportion, now gone bust.

Greenspan vs. Bernanke

Note the huge difference in the problems of Greenspan as compared to Bernanke.

Greenspan had the winds of rising productivity in conjunction with an internet boom, followed by the winds of housing and commercial real estate booms, blowing at his back. The internet boom and the housing bubble both provided an enormous source of jobs.

In contrast, Bernanke has a gale force breeze of a secular change in social attitudes towards debt in conjunction with unfavorable boomer demographics, blowing briskly in his face. There is no source of jobs now, only the hollow shells of vacant commercial real estate standing as testimony to the blatantly foolish policies of the Greenspan and Bernanke Fed.

Inflationists simply do not understand the importance of these secular shifts in consumer attitudes and demographics.

Luck of the Draw

Greenspan was "lucky" in the sense that the credit booms fueled asset prices as opposed to consumer prices. Greenspan never had to act to contain "inflation" because he failed to see any even though it fueled a massive asset bubble in housing and commercial real estate.

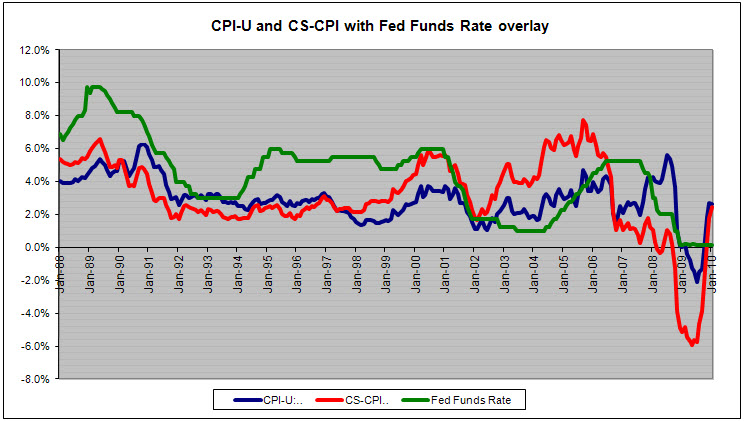

Here is a chart from Case-Shiller CPI Now Tracking CPI-U that shows what I mean. http://globaleconomicanalysis.blogspot. ... cpi-u.html

CS-CPI vs. CPI-U

The above chart compares CPI-U vs. CS-CPI, the latter formed by substituting the Case-Shiller home price index for OER (Owners' Equivalent Rent), in the CPI. Home prices were relatively stable in the mid-to-late 90's as the real cost of borrowing was high.

However, note what happened when Greenspan held rates low in 2002-2006. Real interest rates (subtract CS-CPI from the Fed Funds Rate) were as low as NEGATIVE 5% in 2004.

Is it any wonder asset prices soared?

This is one of many reasons why Bernanke's 2% "inflation" policy is preposterous. The Fed simply has no control where liquidity flows, or for that matter if there is a flow at all. Note that real interest rates as measured by CS-CPI hit POSITIVE 6% in 2009 in the wake of the housing crash. Ironically, talk of the town was "massive inflation".

The above chart is from March 5, 2010. Although real interest rates are now negative by my measure, I do expect home prices as measured by Case-Shiller to start dropping this autumn, and for real interest rates to be positive once again, even at a 0% Fed Funds rate!

Aftermath of the Credit Bubble Bust

Greenspan and Bernanke both failed to spot the massive increase in inflation in the early 2000's because liquidity flowed into assets as opposed to wages and consumer prices. We are now in the aftermath of the credit bubble bust.

Just as rising productivity and rising asset prices masked massive inflation of money supply and credit in the early 2000's, the reported CPI-U masked falling home prices (and high real interest rates) from 2006 on.

With consumers deleveraging, boomer demographics, and no driver for jobs or economic growth, wages and prices are highly likely to be contained.

Thus, Levy has the result correct (deflation) but missed the key reason why - a secular change in consumer attitudes towards credit and debt in conjunction with a secular shift in the attitudes of banks' willingness to lend.

Levy:

2. Why Aggressive Monetary Policy Isnât Causing and Wonât Cause Inflation

The notion of an inexorable link between monetary policy and inflation is pounded into our brains by the prevailing economic wisdom: âinflation is a monetary phenomenon,âJoin our efforts to Secure America's Borders and End Illegal Immigration by Joining ALIPAC's E-Mail Alerts network (CLICK HERE)

LinkBack URL

LinkBack URL About LinkBacks

About LinkBacks

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Massachusetts House Democrats Vote Against Bill to Prioritize...

04-30-2024, 12:09 PM in illegal immigration News Stories & Reports