Results 1 to 9 of 9

Thread Information

Users Browsing this Thread

There are currently 1 users browsing this thread. (0 members and 1 guests)

Hybrid View

-

01-27-2008, 09:25 PM #1

- Join Date

- Jan 1970

- Posts

- 35

Sen. John C. Calhoun Vetoes Annexation of Mexico (1848)

This historical speech arguing against the annexation of Mexico features some politically incorrect ideas as spoken by Sen. Calhoun in 1848, my apologies if this offends any patriots here, this was from the slavery era, however if you can get past that any history buffs here might find this one interesting:

Former VP Warned America Against Trying to Annex Mexico

John C. Calhoun foresaw today’s problems in 1848

A fact of history unknown to most Americans today is that Congress once debated a proposal to annex all of Mexico. Following the conclusion of the Mexican War in 1848, Mexico, utterly defeated by American forces, was under U.S. military occupation. Expansion-minded lawmakers began to contemplate simply retaining the army’s conquests and extending our southern border all the way to Guatemala. One who disagreed with this idea–and whose position ultimately prevailed–was Senator John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, who had earlier been Vice President of the United States under President Jackson.

Calhoun understood that the acquisition of Mexico would turn America into a multiracial state, fundamentally altering its character. In his speech before the Senate arguing against annexation, he identified both the essence of American nationality and the perquisites for the freedom that Americans enjoyed. As today’s Americans suffer under the present invasion of Mexican migrants that their leaders refuse to repel, Calhoun’s words have special relevance:

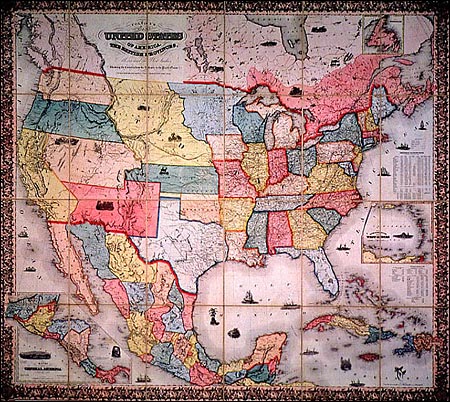

Instead of annexing Mexico, the Senate instead ratified the treaty that the State department negotiated with Mexican authorities at Guadalupe Hidalgo. Under the treaty, the United States acquired the southwestern fourth of its present territory, an area that at the time was nearly uninhabited. In return, the United States–the undisputed victor in the war and master of Mexico–relinquished its control over the that country and compensated the Mexicans for their loss with an indemnity of $15 million–a huge sum in 1848.…The next reason which my resolutions assign, is, that it is without example or precedent, wither to hold Mexico as a province, or to incorporate her into our Union. No example of such a line of policy can be found. We have conquered many of the neighboring tribes of Indians, but we have never thought of holding them in subjection—never of incorporating them into our Union. They have either been left as an independent people amongst us, or been driven into the forests.

I know further, sir, that we have never dreamt of incorporating into our Union any but the Caucasian race—the free white race. To incorporate Mexico, would be the very first instance of the kind of incorporating an Indian race; for more than half of the Mexicans are Indians, and the other is composed chiefly of mixed tribes. I protest against such a union as that! Ours, sir, is the Government of a white race. The greatest misfortunes of Spanish America are to be traced to the fatal error of placing these colored races on an equality with the white race. That error destroyed the social arrangement which formed the basis of society. The Portuguese and ourselves have escaped—the Portuguese at least to some extent—and we are the only people on this continent which have made revolutions without being followed by anarchy. And yet it is professed and talked about to erect these Mexicans into a Territorial Government, and place them on an equality with the people of the United States. I protest utterly against such a project.

Sir, it is a remarkable fact, that in the whole history of man, as far as my knowledge extends, there is no instance whatever of any civilized colored races being found equal to the establishment of free popular government, although by far the largest portion of the human family is composed of these races. And even in the savage state we scarcely find them anywhere with such government, except it be our noble savages—for noble I will call them. They, for the most part, had free institutions, but they are easily sustained among a savage people. Are we to overlook this fact? Are we to associate with ourselves as equals, companions, and fellow-citizens, the Indians and mixed race of Mexico? Sir, I should consider such a thing as fatal to our institutions.

The next two reasons which I assigned, were, that it would be in conflict with the genius and character of our institutions, and subversive of our free government. I take these two together, as intimately connected; and now of the first—to hold Mexico in subjection.

Mr. President, there are some propositions too clear for argument; and before such a body as the Senate, I should consider it a loss of time to undertake to prove that to hold Mexico as a subjected province would be hostile, and in conflict with our free popular institutions, and in the end subversive of them. Sir, he who knows the American Constitution well—he who has duly studied its character—he who has looked at history, and knows what has been the effect of conquests of free States invariably, will require no proof at my hands to show that it would be entirely hostile to the institutions of the country to hold Mexico as a province. There is not an example on record of any free State even having attempted the conquest of any territory approaching the extent of Mexico without disastrous consequences. The nations conquered have in time conquered the conquerers by destroying their liberty. That will be our case, sir. The conquest of Mexico would add so vast an amount to the patronage of this Government, that it would absorb the whole power of the States in the Union. This Union would become imperial, and the States mere subordinate corporations. But the evil will not end there. The process will go on. The same process by which the power would be transferred from the States to the Union, will transfer the whole from this department of the Government (I speak of the Legislature) to the Executive. All the added power and added patronage which conquest will create, will pass to the Executive. In the end, you put in the hands of the Executive the power of conquering you. You give to it, sir, such splendor, such ample means, that, with the principle of proscription which unfortunately prevails in our country, the struggle will be greater at every Presidential election than our institutions can possibly endure. The end of it will be, that that branch of Government will become all-powerful, and the result is inevitable—anarchy and despotism. It is as certain as that I am this day addressing the Senate.

But, Mr. President, suppose all these difficulties removed; suppose these people attached to our Union, and desirous of incorporating with us, ought we to bring them in? Are they fit to be connected with us? Are they fit for self-government and for governing you? Are you, any of you, willing that your States should be governed by these twenty-odd Mexican States, with a population of about only one million of your blood, and two or three millions of mixed blood, better informed, all the rest pure Indians, a mixed blood equally ignorant and unfit for liberty, impure races, not as good as Cherokees or Choctaws?

We make a great mistake, sir, when we suppose that all people are capable of self-government. We are anxious to force free government on all; and I see that it has been urged in a very respectable quarter, that it is the mission of this country to spread civil and religious liberty over all the world, and especially over this continent. It is a great mistake. None but people advanced to a very high state of moral and intellectual improvement are capable, in a civilized state, of maintaining free government; and amongst those who are so purified, very few, indeed, have had the good fortune of forming a constitution capable of endurance. It is a remarkable fact in the history of man, that scarcely ever have free popular institutions been formed by wisdom alone that have endured.

It has been the work of fortunate circumstances, or a combination of circumstances—a succession of fortunate incidents of some kind—which give to any people a free government. It is a very difficult task to make a constitution to last, though it may be supposed by some that they can be made to order, and furnished at the shortest notice. Sir, this admirable Constitution of our own was the result of a fortunate combination of circumstances. It was superior to the wisdom of the men who made it. It was the force of circumstances which induced them to adopt most of its wise provisions. Well, sir, of the few nations who have the good fortune to adopt self-government, few have had the good fortune long to preserve that government; for it is harder to preserve than to form it. Few people, after years of prosperity, remember the tenure by which their liberty is held; and I fear, Senators, that is our own condition. I fear that we shall continue to involve ourselves until our own system becomes a ruin. Sir, there is no solicitude now for liberty. Who talks of liberty when any great question comes up? Here is a question of the first magnitude as to the conduct of this war; do you hear anybody talk about its effect upon our liberties and our free institutions? No, sir. That was not the case formerly. In the early stages of our Government, the great anxiety was how to preserve liberty; the great anxiety now is for the attainment of mere military glory. In the one, we are forgetting the other. The maxim of former times was, that power is always stealing from the many to the few; the price of liberty was perpetual vigiliance. They were constantly looking out and watching for danger. Then, when any great question came up, the first inquiry was, how it could affect our free institutions—how it could affect our liberty. Not so now. Is it because there has been any decay of the spirit of liberty among the people? Not at all. I believe the love of liberty was never more ardent, but they have forgotten the tenure of liberty by which alone it is preserved.

We think we may now indulge in everything with impunity, as if we held our charter of liberty by "right divine"—from Heavan itself. Under these impressions, we plunge into war, we contract heavy debts, we increase the patronage of the Executive, and we even talk of a crusade to force our institutions, our liberty, upon all people. There is no species of extravagance which our people imagine will endanger their liberty in any degree. But it is a great and fatal mistake. The day of retribution will come. It will come as certainly as I am now addressing the Senate; and when it does come, awful will be the reckoning—heavy the responsibility somewhere!

Sen. John C. Calhoun 1848

Additional:

Images of the U.S.-Mexican War

An Interesting U.S.-Mexican War Website

Gen. Scott hoists Old Glory over National Palace of Mexico

Franklin Pierce’s Journal on the March from Vera Cruz

Descendants of Mexican War Veterans Website

Gen. Winfield Scott’s Entrance into Mexico City Sept. 1847

The Mexican-American War 1846 -1848

Map of the United States & Mexico following the war

LinkBack URL

LinkBack URL About LinkBacks

About LinkBacks

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Democratic town furious over migrant shelter opening in...

05-19-2024, 09:31 AM in illegal immigration News Stories & Reports