Results 1 to 2 of 2

Thread Information

Users Browsing this Thread

There are currently 1 users browsing this thread. (0 members and 1 guests)

-

02-11-2007, 11:36 AM #1Senior Member

- Join Date

- Jun 2005

- Location

- North Carolina

- Posts

- 8,399

Fugitive Honduran street gang leader may be in Houston

http://www.chron.com/disp/story.mpl/met ... 43500.html

Feb. 11, 2007, 1:21AM

Fugitive Honduran street gang leader may be in Houston

By SUSAN CARROLL

Copyright 2007 Houston Chronicle

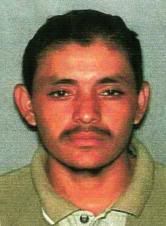

Aliases: Lester Rivera Paz, Franklin Jairo Rivera Hernandez

Nicknames: El Culiche, the Little Baby, El Viejo

Age: 31

Height: 5' 8"

Weight: 175 lbs

Tattoos: MS; LA; Tombs; NLS, short for Normandie Locos Salvatrucha

Fugitive gang leader

Honduras bus massacre

MS-13 BASICS

Mara Salvatrucha originated in Los Angeles in the 1980s. The first members were Salvadoran refugees who banded together to combat other street gangs, but the ranks grew to include Guatemalans and Hondurans.

The National Drug Intelligence Center estimates there are between 8,000 and 10,000 "hard-core members" in the U.S. The FBI has identified members in more than 30 states, with the largest cells in Houston, Los Angeles, New York and Washington, D.C.

The international membership estimates range from 30,000 to 50,000.

The FBI has formed a national task force to combat MS-13, calling it one of the most dangerous street gangs in America.

The task force is working to establish a comprehensive database that merges detainees' criminal records from the U.S. and Central American countries.

Anyone with information on gang members or activity in Houston is asked to call the FBI at 713-693-5000 or the National Gang Task Force at 202-324-5341.

TIMELINE

Oct. 8, 1975: Ever Anibal Rivera Paz is born in San Francisco de Yojoa, Honduras.

Nov. 30, 1993: First U.S. arrest in San Francisco on drug charge.

Jan. 27, 1996: Deported from Los Angeles.

Sept. 6, 1996: Deported from San Francisco.

March 11, 1997: Deported from L.A.

June 25, 2001: Convicted of presenting a false ID to police officers, 13 days confinement.

Aug. 15, 2001: Deported from L.A.

July 31, 2003: Imprisoned in Comayagua, Honduras

Aug. 17, 2004: Escaped from prison.

Dec. 23, 2004: Twenty-eight people die in a massacre in Chamelecon.

Jan.-Feb. 2005: Hondurans warn Rivera Paz may be headed north.

Feb. 8, 2005: Department of Homeland Security issues an alert.

Feb. 10, 2005: Detained by Texas state trooper.

July 8, 2005: Sentenced to seven months.

Nov. 17, 2005: Deported to Honduras.

April 10, 2006: Interpol issues alert.

May 2006: FBI issues alert.

Source: Records; Chronicle research based on records from and/or interviews with Interpol, FBI, Honduran Security Ministry, Honduras' General Bureau for Criminal Investigation, U.S. District Court, U.S. Border Patrol, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement

TEGUCIGALPA, HONDURAS A reputed killer and leader of one of the world's most notorious street gangs escaped during a botched custody transfer in Honduras and has been a fugitive for more than a year, the Houston Chronicle has learned.

Ever Anibal Rivera Paz, the alleged chief of the Honduran arm of the Mara Salvatrucha gang, was being extradited on charges of plotting a massacre that left 28 people, including six children, dead on Dec. 23, 2004.

Also known as "El Culiche," The Tapeworm, Rivera Paz was last seen boarding a deportation flight from Houston to Honduras on Nov. 17, 2005, according to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement records.

The FBI fears Rivera Paz may have returned to the United States or may be headed that way, according to a confidential May 2006 FBI bulletin obtained by the Chronicle.

"Officers should be aware that he has threatened to assassinate any officer that attempts to apprehend him," the bulletin states.

Honduran officials confirmed Rivera Paz's disappearance but said they were never notified that he was scheduled for deportation.

U.S. immigration officials insisted that the Honduran government was notified in writing through multiple channels that "Culiche" was headed back after a stint in a U.S. prison for re-entering the country illegally.

"I don't want to blame anybody," said Oscar Alvarez, former security minister for Honduras, "but somebody didn't do his job."

Nine months before Rivera Paz disappeared, top FBI officials and then-President of Honduras Ricardo Marduro called news conferences to announce his capture. He was arrested by a Texas state trooper near Falfurrias on Feb. 10, 2005, after a traffic stop about 110 miles from the border.

Twelve days after the arrest, U.S. officials matched Rivera Paz to a Department of Homeland Security alert, based on Honduran intelligence, that warned he could be heading north to avoid prosecution in the massacre. His arrest was called a major blow to Mara Salvatrucha, or MS-13, and a model of international cooperation.

Now, two years after his arrest, the Rivera Paz case has raised serious questions about security procedures in both countries and about the integrity of the deportation process.

U.S. and Honduran officials could not, or would not, explain exactly how he escaped.

When the alleged MS-13 leader was deported, "nobody advised anybody" that he was coming home, said Alvarez, now the vice consul in Houston. The problem wasn't just on the U.S. side, he added, conceding that Hondurans also failed to catch his arrival.

Luisa Deason, an ICE spokeswoman in Houston, said U.S. authorities notified the Honduran government that Rivera Paz would be deported that day. She said ICE listed his name on a roster of deportees arriving in Honduras who had criminal records in the United States. The Honduran government also issued travel papers for Rivera Paz, she said, clearing the way for his deportation.

"We executed that removal order and turned everyone on that flight over to the government," Deason said. "If there's a question after that, perhaps what you need to do (is) ask that government."

The international law enforcement organization Interpol has reissued a lookout for Rivera Paz, who is described as ''extremely dangerous."

On the night of the 2004 massacre, Alvarez arrived at the crime scene to coordinate the manhunt for the assailants, who had ambushed a crowded bus.

There were bodies in the road, blood on the bus steps. The killers left a note on the front windshield decrying a government proposal to legalize the death penalty as part of a crackdown on gangs.

"I don't want to remember," he said. "It was a terrorist attack."

At 7:15 p.m., an old, yellow Ford bus headed along a dirt road that runs through Chamelecon, a poor suburb of San Pedro Sula in northern Honduras. The bus was packed with 56 people, factory workers and last-minute Christmas shoppers, some standing in the aisle.

Witnesses said a truck and a car pulled out of the darkness, forcing the bus to the shoulder next to a grassy soccer field. The gunmen started shooting from outside the bus, the witnesses said, and then moved up the steps.

"People were screaming, and the more they screamed in the bus, the more they shot," said a teenage factory worker who was shot 16 times.

Alvarez said witnesses on the bus identified one of the gunmen as Rivera Paz. They said he was carrying an M-16 rifle.

Oldin Alexander Rodriguez, a young father, was in the 13th row with his wife and their baby, Isaac.

It was dark on the bus, he said. So dark he never saw a thing. But he heard people screaming and dropping to the floor.

He wrapped his hulking body around his wife, Glenda Yaqueline Ramos, who pulled Isaac into her lap. She shielded him with her knees, her arms and her head. She tried not to scream.

When international travelers tourists, missionaries and business travelers arrive at the newly remodeled airport in Tegucigalpa, they are required to pass through a Honduran customs inspection. They are asked to show their passports. They put their right, then left, index fingers on a digital scanner. They look up at the camera to have their retinas scanned.

It's different for Hondurans deported from the U.S.

They are corralled into a low-slung, beige building off the runway. There is no fingerprint scanner. The recent arrivals fill out forms with their names, ages and dates of birth. The paperwork is filed away in three-ring binders by date of arrival.

Honduran immigration officials said they are poorly equipped to deal with a record influx of deportees from the U.S., more than 24,000 in 2006. They don't have money to provide new arrivals with diapers for their babies, much less to hire more staff, said Rosario Murillo, with the Center for Attention to the Returned Migrant.

The system is chaotic. Sometimes the office gets a list of deported criminals, Murillo said, but sometimes it does not. A roster of deported criminals that ICE passed along to Honduran officials early this month contained the names of 59 people accused of offenses including illegal re-entry and sex crimes.

Jorge Bustillo Rivera, who is in charge of fugitive captures for Interpol in Tegucigalpa, reviews the names on the U.S. flight rosters, checks for outstanding warrants in Honduras and tries to detect deportees using aliases.

But Bustillo said he also has to juggle a workload that grows by eight to 10 fugitive cases daily. The nearest FBI office is in El Salvador.

"We don't have the necessary resources to do the job right," Bustillo said.

Rivera Paz must have known the drill when the plane landed on Nov. 17, 2005.

It was his fifth deportation flight.

No one's sure how long the bus attack lasted that night. Some passengers said two minutes. Others said five.

Alexander, the young father, was shot in the leg and side. The bullets ricocheted around inside his torso.

His 23-year-old wife felt his body go limp. She panicked and raised herself up, screaming. A bullet hit her right shoulder first. She was hit again, and stopped moving.

Alexander regained consciousness but still saw nothing, he said. He heard a stranger's voice, one of the attackers, moving methodically through the bus. The gunman paused over people who were still breathing, Alexander recalls. He'd ask, "Are you still alive?" Then he would shoot.

Alexander checked on his family. His wife still wasn't moving. The baby in her lap was covered in blood.

U.S. investigators described Rivera Paz as intelligent, articulate and highly mobile. They said he uses different birth dates but is thought to be about 31.

He carries fake IDs, uses multiple cell phones and has 38 known aliases, according to Honduran authorities and the FBI. He has a number of nicknames in addition to "The Tapeworm," including ''The Little Baby."

An early member of the Normandie Locos, a particularly violent Los Angeles-based clique, Rivera Paz's criminal history dates to the early 1990s. He's been arrested at least eight times in California, accused of drug trafficking, aggravated assault, burglary, using fake IDs, writing bad checks and driving without a license, according to federal law enforcement sources.

But most of the serious charges were dropped or sealed in his juvenile record. His convictions in the U.S. were relatively minor: misdemeanor burglary in San Francisco, false representation to a police officer in Los Angeles and giving law enforcement a fake ID in San Luis Obispo. He served 13 days in jail in California in 2001, according to his federal court complaint.

Rivera Paz was deported twice in 1996, once in 1997 and again in 2001.

In 2003, he was arrested in Comayagua, Honduras, allegedly with 19 marijuana joints, 29 baggies of cocaine and an AK-47 in his possession, according to Honduran court records. The documents also referred to an outstanding warrant in two murders in 2003 in Comayagua, allegedly of a woman and teenager who wanted out of the gang. The disposition of those cases was unclear.

The intelligence report in the Interpol file accuses Rivera Paz and his associates of hiring out their services as kidnappers, drug traffickers and hitmen.

"These gangs in Honduras aren't just gangs anymore," Bustillo said. ''They're linked to organized crime."

According to Honduran court records, Rivera Paz claimed to have retired from the gang life after his mother died, telling the judge, "I declare myself innocent of everything."

On Aug. 17, 2004, he and two other inmates allegedly broke out of a prison in Comayagua, beating and severely injuring a guard in the process, according to Interpol.

It was in that picturesque, colonial town that the MS-13 leaders reportedly plotted the massacre.

Honduran investigators said they've identified seven suspects directly involved and 24 with possible knowledge of it. They still call Rivera Paz the mastermind behind the attack.

A handful of Rivera Paz's alleged accomplices are on trial in San Pedro Sula.

After Rivera Paz's arrest in South Texas, he went before a judge in federal court in Houston to face a charge of unlawfully re-entering the country. He pleaded guilty.

On July 8, 2005, U.S. District Court Judge David Hittner sentenced him to seven months in prison in line with federal sentencing guidelines. Much of his federal court file remains sealed.

When he appeared before the judge, Rivera Paz said: "Please, send me back to my own country to pay for the crimes I caused there."

On Christmas Day 2004, the families of Chamelecon buried their dead, including 16 women and six children. One of the women was three months pregnant.

There are still questions about the motives behind the massacre. Some are convinced it was a gesture of defiance against Honduran authorities. Others say it was revenge against a rival gang.

In their tin-roofed house on the outskirts of San Pedro Sula, Alexander gently tucks a stray hair behind Yaqueline's ear, on the side of her head that she can't reach because of her injuries. Their son, Isaac, now 3, wears SpongeBob SquarePants T-shirts and chases around the puppy, ''Bear."

Yaqueline pushes her wheelchair with her good arm, the strong one.

She is not expected to walk again.

A while ago, the prosecutor in the trial of the other MS-13 members came by their house. He was looking for witnesses.

"I told him, we didn't see a thing," Alexander said.

Yaqueline nodded.

"It was so dark. I didn't see a thing."Join our efforts to Secure America's Borders and End Illegal Immigration by Joining ALIPAC's E-Mail Alerts network (CLICK HERE)

-

02-11-2007, 12:51 PM #2

This guy's been deported 5 times?! 28 people murdered, and God knows what he's done in this country. If he's in Houston I hope he's caught there. Texas doesn't wait 40 years before they execute murderers. Seems deportation will do nothing in this guy's case.......mod edit.

LinkBack URL

LinkBack URL About LinkBacks

About LinkBacks

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Listen to Frosty Wooldridge on Rense Apr 23, 2024 talking...

04-24-2024, 05:17 PM in illegal immigration News Stories & Reports