Results 1 to 1 of 1

Thread Information

Users Browsing this Thread

There are currently 1 users browsing this thread. (0 members and 1 guests)

-

04-18-2019, 12:01 AM #1

How One Houstonian Almost Lost Everything When It Was His Word Against Border Officia

How One Houstonian Almost Lost Everything When It Was His Word Against Border Officials

“There’s no justice for the immigrant,” Elvin said, after border officials wrote in legal documents that he had recently crossed the border. Despite having lived here for more than a decade, Elvin was detained for months and almost deported. Back in Houston, his pregnant wife spent their savings on legal aid while taking care of their two kids.

Elizabeth Trovall | Posted on April 17, 2019, 5:00 PM

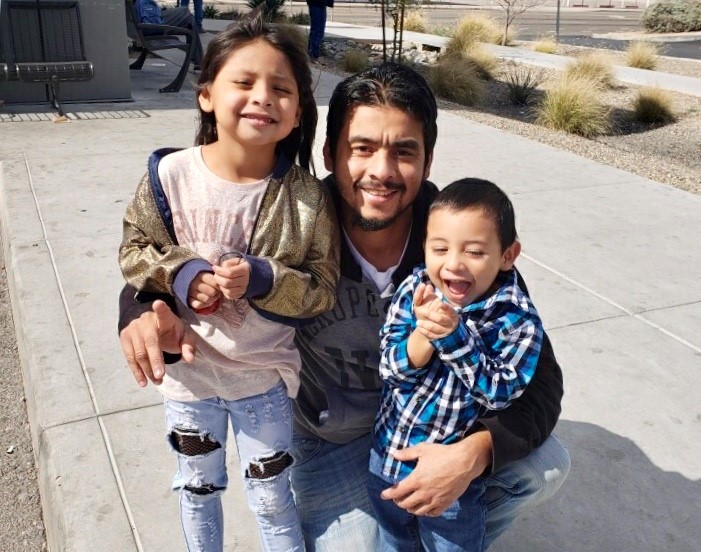

Courtesy of Elvin

Courtesy of Elvin

Elvin embraces his two kids after being in immigrant detention for two months. Isabel was expecting her third child with her husband Elvin when their lives unexpectedly started to unravel.

Elvin, a welder living in Houston, went to Laredo last December to scout out a job opportunity.

On his way back home, his bus stopped at a Border Patrol checkpoint. These checkpoints within the 100-mile zone of the border allow for immigration authorities to question anybody about their legal status, even though they’re not at a port of entry.

Immigration officials detained Elvin, who’s undocumented and from Honduras.

They took him to what’s referred to in Spanish as a hielera or “icebox”, a Customs and Border Protection holding facility.

“They put you in a extremely cold room,” said Elvin in Spanish.

Elvin said officers questioned him for hours. He refused to talk at first, since he didn’t have a lawyer with him.

Officials came forward with paperwork and a photo of another Honduran man with his same name who had already been deported, according to Elvin. He said that wasn’t him — they were wrong.

Then, border agents came to Elvin with other questions, like if he drove an Infiniti and had a pending immigration petition.

Elvin said, yes, that was him. He did have an petition.

“I’ve never been deported,” said Elvin. “I’ve lived in this country since 2007.”

But in documents shared with Houston Public Media, Border Patrol agents wrote down that Elvin said he crossed the river into the U.S. near Laredo five days prior, on December 15, 2018.

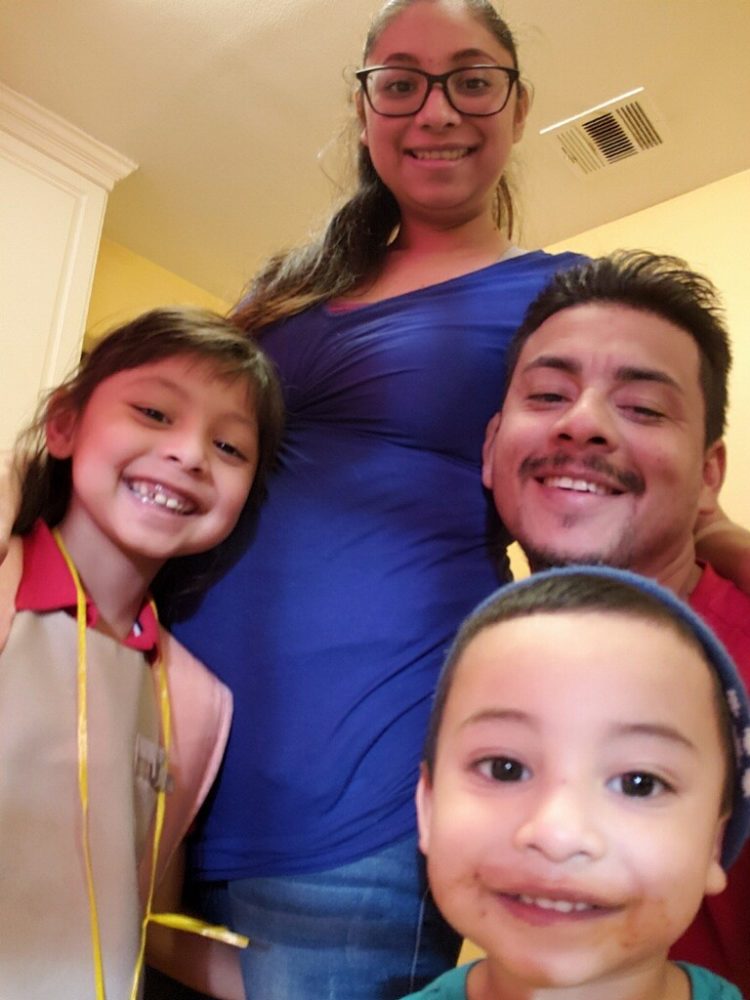

Courtesy of Elvin

Courtesy of Elvin

Isabel, two months pregnant, with her husband Elvin and their two kids. People who have crossed the border within 14 days can be ordered deported through what’s called “expedited removal.”

That specific timing is crucial in the world of immigration enforcement.

It’s a way to speed up the deportation of people who have recently entered by taking away their right to appeal their deportation.

But Elvin hadn’t recently crossed the border, so he shouldn’t have been eligible for expedited removal, according to federal immigration rules. And Elvin had a strong case for staying legally in the United States and the right to plead his case before a judge: he has two citizen children, his wife is protected by Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and his father is a U.S. citizen. As he discussed with border officers, Elvin already had a petition pending to gain legal status.

Houston Public Media reached out to Customs and Border Protection for comment and they have not responded.

After refusing to sign any papers, Elvin was locked away and sent to a detention center in San Antonio.

Back in Houston, Isabel didn’t hear from him for five days until she finally received a call from him: her husband was in trouble.

Using their family savings, Isabel spent thousands on an immigration lawyer.

Battling pregnancy symptoms like dizziness and nausea, Isabel rushed around town to get papers to prove her husband had been living in Houston.

“I [felt] dizzy and I still had to drive to go see the lawyer. It happened twice I had to stop in the middle of the freeway,” said Isabel.

Listen

00:00 /04:02

To embed this piece of audio in your site, please use this code:

<iframe src="https://embed.hpm.io/329582/329384" style="height: 115px; width: 100%;"></iframe>

X

But every legal action failed as weeks passed.

In Houston, Isabel’s kids missed their dad as she tried to comfort them.

“When my son woke up in the morning he was asking, ‘Dad didn’t give me a kiss… Where is Daddy because he didn’t give me kiss?” Isabel said. “Remembering those words from him, that breaks my heart.”

Elvin was transferred to detention centers in San Antonio, Wisconsin and Illinois, which isn’t uncommon.

In jail, he said there was a two-day delay whenever he asked for pain reliever. He said he spent a lot of time hungry, too, but the worst pain was psychological.

“I spent day and night crying,” Elvin said. Locked away in a tiny cell in an Illinois county jail, his mind was racing. At this point, several weeks had passed, and he was still facing deportation.

“It’s all over,” he said he would say to himself. “What am I going to do now? They’re going to send me to my country. My kids are going to stay here. Who is going to help them?”

A rare case?

In some ways, Elvin’s case is unique.

Julie Pasch, an attorney with the Houston Immigration Legal Services Collaborative, said that she’s never seen anybody with his background be erroneously put in expedited removal proceedings.

But, that doesn’t mean it’s not happening, she said.

“What’s concerning me is that if this is happening to him, how many other people is it happening to [who] didn’t have access to an attorney, who didn’t have the chance to push back?”

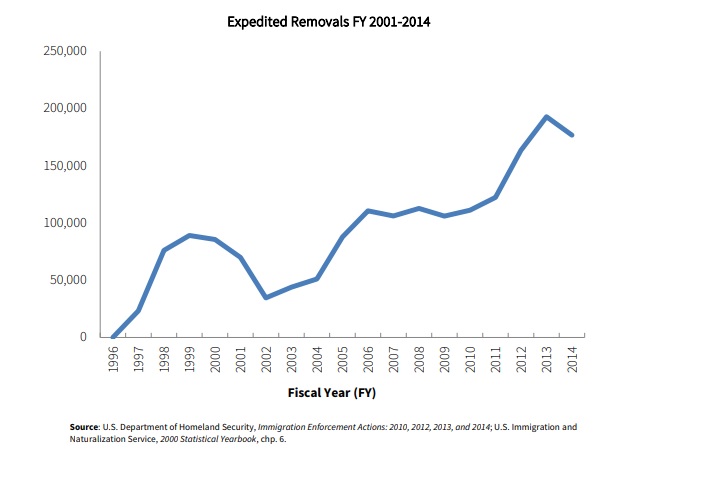

U.S. Department of Homeland Security data compiled by the American Immigration Council

U.S. Department of Homeland Security data compiled by the American Immigration Council

The use of expedited removal has grown since it was first created in 1996. Pasch also said that she frequently sees errors in immigration documents coming from the border zone.

“Finding either outright falsifications or errors — and often time it’s difficult to tell which — on documents prepared by Customs and Border Protection is extremely common,” Pasch said.

She said that she’s seen a high percentage of clients with errors on their documents. For example, she often talks with clients with paperwork that says they were coming to the U.S. to work, when the client says they actually left out of fear for their lives.

Asylum laws protect people with fears of returning to their home countries because of violence. Economic strife is not protected, so having incorrect documentation could impact the outcome of someone’s asylum claim.

Pasch also said it’s important to consider that the border zone is a special place where immigration officials have more powers.

“There is so little protection built into the system, particularly for expedited removal, which happens within 100 miles of the border. The American Civil Liberties Union has termed that the ‘constitution-free zone’ and I think this case really demonstrates that,” said Pasch.

Expedited removal was rolled out in 1997 to speed up the processing of undocumented migrants found at the border. Its use has since expanded to apply to any undocumented person found within the 100-mile border zone who entered the country within 14 days.

In 2017, expedited removal was used to deport over 103,000 migrants, according to Department of Homeland Security data.

It looked like Elvin would be another one of the thousands deported through expedited removal.

National Immigrant Justice Center

National Immigrant Justice Center

After being released from detention, Elvin (center) stands with National Immigrant Justice Center lawyers (left to right), Guadalupe Perez, Hannah Cartwright, Hena Mansori and Chuck Roth. One last shot

In Houston, Isabel had gone through all their savings, and she couldn’t make rent. Now midway through her pregnancy, she was rejected when she asked for work.

With no income and now no savings, they had to abandon most of their furniture and belongings and quickly move away from Houston.

“I know it’s something material, but it’s something that we work a lot to get,” Isabel said. “I cried when I saw all my things outside of the house.”

Their only option was to move in with Isabel’s family in Tucson, Arizona.

All was lost, they thought.

Courtesy of Elvin

Courtesy of Elvin

Elvin reunites with wife and kids at a bus station in Tucson after he is released from Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention. Then some lawyers from the Chicago-based National Immigrant Justice Center filed a special motion after learning about Elvin’s case. Days before his flight to Honduras, they showed a federal judge proof Elvin had been living here: his marriage certificate, tax returns, a credit card statement and other documents.

The judge cancelled his deportation.

“I was really really happy that I screamed,” Isabel said.

Nearly two months had passed, but Elvin was released mid-February. He took a bus to Arizona to their family’s new temporary home.

Isabel took her kids to the bus terminal without saying they would be reunited with her dad.

“I saw the bus when it parked in the parking lot and I said, ‘Stand up to see if there’s someone familiar to you,’” she said.

Her two kids finally recognized Elvin and ran towards their dad to hug him.

They may have lost their home, but they didn’t lose their family.

https://www.houstonpublicmedia.org/a...der-officials/You've got to Stand for Something or You'll Fall for Anything

Similar Threads

-

Word for Word: Homeland Security Secretary Nielsen Announces New Asylum Policy

By stoptheinvaders in forum General DiscussionReplies: 5Last Post: 01-30-2019, 09:12 AM -

DPS list identifies spillover crimes in Texas; local officia

By Jean in forum illegal immigration News Stories & ReportsReplies: 1Last Post: 05-29-2011, 07:55 PM -

AZ-Sheriff Arpaio releases tapes of deputies and ICE officia

By FedUpinFarmersBranch in forum illegal immigration News Stories & ReportsReplies: 16Last Post: 07-27-2009, 02:49 PM -

Poll: Why are Immigration Laws Ignored by our Public Officia

By AirborneSapper7 in forum Polls & Surveys About Illegal ImmigrationReplies: 1Last Post: 04-27-2009, 09:51 AM -

N.C. Office To Open For Kids Arrested By Immigration Officia

By JohnB2012 in forum illegal immigration News Stories & ReportsReplies: 4Last Post: 10-31-2006, 01:09 PM

LinkBack URL

LinkBack URL About LinkBacks

About LinkBacks

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Durbin pushes voting rights for illegal aliens without public...

04-25-2024, 09:10 PM in Non-Citizen & illegal migrant voters