Results 1 to 6 of 6

Thread Information

Users Browsing this Thread

There are currently 1 users browsing this thread. (0 members and 1 guests)

-

08-27-2018, 11:27 PM #1

Life in Caracas (Venezuela)

Life In Caracas

Life Without Water: Sweaty, Smelly, and Furious in Caracas

This has to be the most egalitarian disaster the socialist government has managed to engineer yet.

By Andrew Rosati

August 27, 2018, 5:00 AM CDT

Caracas Water Shortage

Editors Note: There are few places as chaotic or dangerous as Venezuela. “Life in Caracas” is a series of short stories that seeks to capture the surreal quality of living in a land in total disarray.

https://www.bloomberg.com/life-in-caracas-venezuela

When I’m lucky, a trickle flows through my apartment building’s rickety pipes. When I’m really lucky, they deliver as much as 30-straight minutes worth of H2O. That’s enough to fill up the 200-or-so-gallon tank in my kitchen and trigger a celebration.

I’ll do something crazy and run the water until it gets really hot before I jump into the shower.

The tank is hooked up to the building’s distribution system, so I don’t have to be present to collect the precious liquid. In past rentals, I had no net. I did the mad Caracas water dash when the pipes mysteriously started flowing while I was home. I’d fill buckets, pots, coffee mugs—anything.

Venezuelans have struggled with access to potable, running water for years. But in 2018, the water crisis spread across the country, affecting everyday life for all citizens.

Photographer: Adriana Loureiro Fernandez/Bloomberg

True enough, in Caracas, we go without reliable access to an extensive list of basic life essentials, from toilet paper to toothpaste. But if you ask me, dry taps are by far the most unpleasant of the epic shortages.

Dishes are brushed off and reused, and clothing is not something regularly laundered, though, personally, I draw the line at multiple wearings of underwear or socks. You ask friends whether it’s okay to flush. You often do not. We’re sweaty and, yes, smelly, especially in the rainy season when the humidity can top 80 percent. We’re at risk, too, because water stagnating in the vessels that people stash around their homes attracts mosquitoes; malaria rates have soared.

The poorest, as usual, have it the worst, though no one is spared. Hospitals and schools, posh neighborhoods and slums, they all go without water—at times for weeks on end—making this man-made drought arguably the most equalizing disaster the socialist government has ever managed to engineer.

For the luckiest neighborhoods, water is rationed to four days a week, but some areas have been without running water for as long as six months. The crisis affects businesses and homes alike, especially those located in slums and poorer areas of the capital.

Photographer: Adriana Loureiro Fernandez/Bloomberg

There’s solidarity in our sticky existence, which is born of crumbling infrastructure. We’re not ashamed to ask to use an acquaintance’s shower, and banging on doors in the wee hours to sound the alert that water has suddenly started flowing isn’t annoying but proof you’re a good neighbor. In a deeply divided nation, protesters of all political stripes have taken to the streets to block traffic and hoist signs saying “Water is a Right.”

For the super-wealthy, a somewhat effective solution has been found. They now dig their own wells. Those a rung or two below them pay to have water trucked in daily by companies that collect it from springs in the surrounding mountains. The needy flock to the springs themselves. They’ll pile children and bottles and tubs into rickety old cars each weekend to make the drive over. And once the containers are filled and the kids are bathed, they head back home.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-08-27/life-without-water-sweaty-smelly-and-furious-in-caracas

Last edited by Newmexican; 08-27-2018 at 11:56 PM.

Support our FIGHT AGAINST illegal immigration & Amnesty by joining our E-mail Alerts at https://eepurl.com/cktGTn

-

08-27-2018, 11:35 PM #2

Economics

Hyperinflation Left Me Broke in Caracas

It’s banking madness in Venezuela, where something as simple as a fast-food meal can cost 20 million bolivars.

By Patricia Laya

August 10, 2018, 5:00 AM CDT

Editors Note: There are few places as chaotic or dangerous as Venezuela. “Life in Caracas” is a series of short stories that seeks to capture the surreal quality of living in a land in total disarray.

I was mesmerized as the cashier at Burger King ran my friend’s debit card.

Whopper, swipe.

Coke, swipe.

Fries, swipe.

Extra barbecue sauce, swipe.

Inflation is now so insane that card-reading devices can’t even ring up a simple fast-food lunch—this one was about 20 million bolivars—without breaking it into small bites. President Nicolas Maduro’s grand plan to fix this situation is to re-denominate the currency and lop off five zeros. He says this will “change the country’s monetary life in a radical way.”

Probably not. But it will at least temporarily ease the madness. There’s not a single business transaction nowadays—paying for a taxi ride or buying a hot dog from a street cart—that’s straightforward and hassle free. Not a one.

As inflation keeps soaring, Venezuelans are relying on credit cards to make simple purchases. However, even this economic work-around has become a struggle.

Photographer: Carlos Becerra/Bloomberg

I mean, I had arrived at the Burger King only because of a bizarre series of events at a restaurant the night before that left me suddenly, and completely, cut off from my cash. It began when the cashier told me that my debit card was declined. And no matter how many times he swiped it, the answer was the same. I called the bank. The fellow on the line informed me that I had reached my withdrawal limit for the month. How much was that? 480 million bolivars. That may sound like a lot, but it’s only about $120.

The cap, he told me, was the banking authority’s way of fighting illicit financial activity. Really. And because credit cards (tiny spending limits) and cash (too cumbersome) have long stopped being viable payment options, I was, as I understood it, penniless for the 11 days until the calendar turned.

This was not real hardship, of course. The rent was paid, the utilities weren’t due. And I had, in fact, managed to eat that Friday night, after the manager was summoned. He agreed to an online bank transfer, though only if I forked over some sort of guarantee until the transaction was confirmed. I handed him my ID and debit card—overnight hostages to a glass of wine and a shrimp-sushi roll.

Burger King, thanks to the generosity of my friend, saw me through Saturday. On Sunday, I went to La Guairita, a neighborhood where vendors sell imported goods long gone from supermarket shelves. All the stuff is astonishingly overpriced, and much of it is way past its sell-by date. The hook, I remembered in my despair, was that I could pay via bank transfer.

Most retailers advertise the acceptance of credit cards. Although, as inflation continues to add zeros to the end of prices, card-readers are easily overburdened with calculating the most straightforward of purchases.

Photographer: Carlos Becerra/Bloomberg

This sudden rush of financial freedom spurred me to to grab more than I needed. Baking powder, why the hell not? Chocolate cereal, sure. The excitement didn’t last long. My bank’s website crashed.

I slumped into a plastic chair in the sun and waited. As I sat there, the rush from buying a bunch of random stuff slowly wore off. I started removing items. First, it was the box of chocolate cereal and a can of soda and then, sadly, a bag of cheese puffs.

After 45 minutes, the transfer mercifully went through. Smiling now, I walked out with the baking powder, some wheat, and a few eggs and bananas. That afternoon, I made banana pancakes. They were great. Or maybe I was just really hungry.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-08-10/venezuelan-hyperinflation-makes-a-fast-food-meal-a-nightmare

Support our FIGHT AGAINST illegal immigration & Amnesty by joining our E-mail Alerts at https://eepurl.com/cktGTn

-

08-27-2018, 11:44 PM #3

There are videos that are not compatible with ALIPACs format at each story.

Business

Where a Bottle of Whisky Costs 16 Years of Wages

Venezuelans give up a symbol of their national identity and turn to local rum.

“Y el whisky?”

They asked again and again, crowding the bar at a wedding reception in a swanky Caracas ballroom, straining to see the bottles. The bartenders wouldn’t budge: Scotch whisky was strictly reserved for the couple’s parents and their friends. For the rest, there was domestic rum.

Rum? Really? It was an insult that didn’t go down well.

A bartender prepares a cocktail with Santa Teresa, a domestic rum.

Photographer: Carlos Becerra/Bloomberg

Now, on the scale of Venezuelan horror stories, this one ranks very, very low. And yet there’s something telling about Caraquenos’ tortured struggle to give up Scotch on the rocks. It's more than just a drink here. It's an age-old status symbol that conjures up memories of the go-go days of the 1970s, when the petrodollars were flowing freely, the government’s debt was rated AAA and Venezuelans were famous—or infamous—for their wild, one-day shopping trips to Miami.

Scotch became part of the national identity, something practically stamped in the DNA of most anyone from the middle class on up. When we pose for pictures, we don’t say “cheese” as the shot’s taken; we say “whisky.” For years, the image of the Johnnie Walker striding man was so omnipresent across Caracas, you’d have thought he was the mayor.

When we wanted to celebrate with family and friends, it was always Scotch, always with shaved ice and a napkin folded snugly around the glass. Rum was for the riffraff. Sipping it now instead of Scotch is like replacing baseball as the national pastime with bowling or, I don’t know, checkers.

Bottles of Scotch on display in a bar in eastern Caracas.

Photographer: Carlos Becerra/Bloomberg

But for most of us there’s no getting around it these days. With inflation soaring above 60,000 percent, a top-shelf liter of Scotch can set you back 1 billion bolivars—a sum that a minimum-wage worker would have to toil 16 years to earn. Even cheap varieties command many, many millions.

“Who can take a hit like that?” said Alfredo Camacho, 24, a college student and part-time sales manager, as he watched a World Cup match in a Caracas pub. He mourned the days when he and his buddies would go out and share a bottle of Buchanan’s, feeling almost patriotic about it. Today he has to settle for rum. Or beer. Or worse. “In these times, I’ve learned to like everything, even cocuy." That’s the stuff that, like tequila, is made from the agave plant but that isn’t quite as, shall we say, smooth.

Liquor stores do stock Buchanan’s and Johnnie Walker Black Label and the like, but a visit to a shop in eastern Caracas brought home how things have changed: Premium rum offerings, such as Ron Carupano’s X.O. or Santa Teresa’s Bicentenario, greeted customers from spinning pedestals; the whisky was in the back.

A bottle of Santa Teresa sits at a customer’s table inside a Caracas restaurant.

Photographer: Carlos Becerra/Bloomberg

The owner told me customers buy 2,500 bottles of rum every month and about 300 bottles of Scotch; not long ago, the numbers were reversed.

A possible upside of the Scotch crisis is that it may be bringing locals around to the excellence of a domestic product so special it’s one of just two in the world that has a denomination-of-origin classification, the other being from Martinique. “We never realized we had such good rum, because it was marginalized,” said Miro Popic, author of “Venezuela on the Rocks.”

Maybe. But I still haven’t heard anyone say “rum” when posing for a picture.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/artic...years-of-wages

Support our FIGHT AGAINST illegal immigration & Amnesty by joining our E-mail Alerts at https://eepurl.com/cktGTn

-

08-27-2018, 11:48 PM #4

Business

Invasion of the Macaws

No one really knows where they all came from, but Caracas is now teeming with exotic birds.

By Noris Soto

June 29, 2018, 5:00 AM CDT

Editors Note: There are few places as chaotic or dangerous as Venezuela. “Life in Caracas” is a series of short stories that seeks to capture the surreal quality of living in a land in total disarray.

The macaw, a big, brilliantly colored and scandalously loud species of parrot, is definitely not indigenous to Caracas.

And yet the bird now seems to be everywhere here.

On a given day, I may spot a pair of them soaring past my window in the morning, a handful on my way into work and a few more as I head home at night. They float in and out of trees and zoom from apartment balcony to apartment balcony—big streaks of neon blue and yellow and green—in search of the scraps of food that their admirers leave out.

Macaws fly over eastern Caracas.

Photographer: Manaure Quintero/Bloomberg

I love them. We all do. In a city where misery is seemingly encountered on every street corner, they provide a brief moment of joy. They’re beautiful, exotic and, like Caraquenos, a little flamboyant. (They also add, I will say, to the post-apocalyptic feel of the place; much of the human population has fled, the buildings have crumbled and the macaws have swooped in.)

But where did they all come from exactly?

That’s something of a mystery. There are many theories. The most common of them posits that the birds were first introduced in the city several decades ago. They were illegally trapped in the rainforests of southern Venezuela and shipped northward as pets.

A Venezuelan feeds macaws on a rooftop.

Photographer: Manaure Quintero/Bloomberg

Macaws, though, aren’t really great companions for cooped-up apartment dwellers. They’re big—about three times as long as a cardinal—and they chatter at full volume. Many people turned them loose, especially as the collapse of the economy started to strain personal finances in recent years.

Today there are four species of macaws living in the wilds of Caracas. Ara ararauna—the blue and yellow variety—is the most common. Malu Gonzalez, a biology professor at Simon Bolivar University, says the macaws have assumed the role of symbol of the city and helped reconnect its inhabitants with nature.

A macaw lands on a rooftop.

Photographer: Manaure Quintero/Bloomberg

“I’m not sure if this has been good for the species,” says Gonzalez, “but for the people, it’s magnificent.” And then she says something that is almost never heard in a country that has been plunged into misery by one public-policy misadventure after another: “Fortunately, this experiment worked out well.”

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-06-29/life-in-caracas-invasion-of-the-macawsSupport our FIGHT AGAINST illegal immigration & Amnesty by joining our E-mail Alerts at https://eepurl.com/cktGTn

-

08-27-2018, 11:54 PM #5

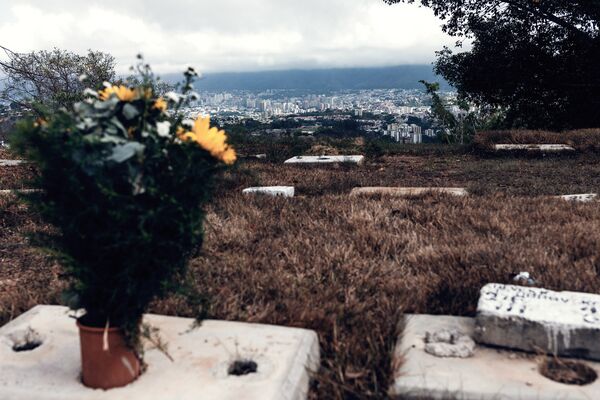

Venezuelan Grave Robbers Are Closing In on My Family

They sneak into the cemetery in the dead of night to snatch the bronze plaques from tombstones.

By Fabiola Zerpa

June 15, 2018, 6:00 AM CDT

When I arrived at the cemetery’s main office, there was a long line of people waiting in the stifling mid-afternoon heat. They had all come to ask the same question I had: Is it true what everyone is saying—are graves really being stripped of their plaques?

Yes, we were told, it is true.

Security personnel patrol Cementerio del Este.

Photographer: Adriana Loureiro Fernandez/Bloomberg

Slowly, one by one, thieves have been prying off the plaques to sell the slabs of bronze in the black market. Graves on the hilly outskirts have been hit the hardest. But there was no need to worry, the cemetery officials told us. They had a plan. They would remove the plaques themselves and replace them with a cheaper material that would be of less value to criminals.

I did not find this very reassuring. I’ve got aunts and uncles and cousins and dear friends buried here in Cementerio del Este. Why should I believe that these new markers won’t just be swiped, too? Am I to just show up hoping I can locate my family members and then stagger around until I think I’m in the right spot? Is nothing sacred in this godforsaken country anymore?

Life here is grim enough already. I’m surrounded by misery. Famine, disease, mob justice, insane inflation. I’m always on edge. And now this?

Yeah, I know grave robbers have been around since the dawn of mankind. I get that. In fact, right here in Caracas, in the public cemetery used by those who can’t afford plots in Cementerio del Este, thieves have been digging up graves for years and selling everything they could get their hands on—from jewels to skeletons (which are sought out for witchcraft).

Flowers were placed on a tombstone stripped of its plaque.

Photographer: Adriana Loureiro Fernandez/Bloomberg

This is precisely what terrifies me, and others, the most. It’s the metal plaques in Cementerio del Este today and skulls and femurs tomorrow.

One woman I encountered in the main office that day told me she had had enough. She had instructed cemetery officials to exhume her parents. She would then have them cremated. And that way, she figured, there really would be nothing left to steal.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/artic...n-on-my-family

Support our FIGHT AGAINST illegal immigration & Amnesty by joining our E-mail Alerts at https://eepurl.com/cktGTn

-

08-28-2018, 07:47 AM #6

Do not bring them here.

Do NOT give them any of our money.

Do NOT go down there...stay out of it.

They can take their oil to pay for and feed themselves.

They have land, they have resources, they have oil, they have a whole ocean full of fish to eat. Give them nothing!

We are not the ATM machine or dumping ground for the world.

We have our own to feed and take care of!

And we are fighting for our lives to STOP the Democrats from destroying our country and turn it into this!

NO VACANCY...ATM MACINE OUT OF ORDER!ILLEGAL ALIENS HAVE "BROKEN" OUR IMMIGRATION SYSTEM

DO NOT REWARD THEM - DEPORT THEM ALL

Similar Threads

-

The Venezuelan Crisis Through the Eyes of a Millennial in Caracas | NowThis

By Newmexican in forum Videos about Illegal Immigration, refugee programs, globalism, & socialismReplies: 0Last Post: 12-30-2017, 02:24 PM -

Venezuela's Middle Class Flees Venezuela for Miami

By AirborneSapper7 in forum General DiscussionReplies: 1Last Post: 03-09-2014, 12:18 AM -

Reckoning in Caracas -Venezuela is running out of other people's money.

By Newmexican in forum Other Topics News and IssuesReplies: 2Last Post: 02-26-2014, 10:27 AM -

U.S. Officials Shot in Caracas Strip Club Incident

By JohnDoe2 in forum General DiscussionReplies: 0Last Post: 05-28-2013, 08:31 PM -

Where's the Poverty?--Caracas video

By Captainron in forum illegal immigration News Stories & ReportsReplies: 1Last Post: 07-15-2009, 02:14 PM

2Likes

2Likes LinkBack URL

LinkBack URL About LinkBacks

About LinkBacks

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Durbin pushes voting rights for illegal aliens without public...

04-25-2024, 09:10 PM in Non-Citizen & illegal migrant voters