Results 1 to 1 of 1

Thread Information

Users Browsing this Thread

There are currently 1 users browsing this thread. (0 members and 1 guests)

-

06-28-2016, 06:01 PM #1

TX - A Border Rancher Explains the Art of Survival

by Jay Root June 28, 2016

Ruperto Escobar on his South Texas ranch along the Rio Grande, the international boundary between the United States and Mexico, in April 2016. For generations, smugglers have used his family's ranch to move people and product across the border, and Escobar doesn't see that changing anytime soon.

ESCOBARES — There are two good hours of sunlight left when Ruperto Escobar points his Ford Super Duty pickup toward the Rio Grande and begins driving down his bumpy ranch road. It’s bumpy on purpose, from strategic neglect, because Escobar doesn’t want to make things easier for the smugglers. It’s already easy enough.

On the way down he explains his ancient ties to this land, extending a sun-beaten hand toward his late grandmother’s stucco house off to the right, then to his cousin’s on the left. Escobar’s forebears founded the town that’s named after them, and he can trace his ancestors back to a 1767 Spanish land grant. Basically everything on this side of Escobar Elementary is theirs.

As the maroon truck moves past fields of hay and alfalfa, Escobar notices the crops could use a little attention, but the truck doesn’t slow down. It dips and rises a few times until, suddenly, a swift and muddy-looking river, fat with spring rain, comes into view.

A smile appears beneath the white cowboy hat. Escobar’s twinkling eyes stare at the watery divide between the United States and Mexico.

“Wow, we’ve got some water on the Rio Grande now,” he says before the truck comes to a stop near his irrigation pump. “That’s good.”

The Rio Grande remains the ranch’s lifeblood, without which his crops would wilt and wither away. It also happens to be a crossing point for drug traffickers, human smugglers and other assorted contraband pushers seeking uninspected passage between Mexico and the United States.

For generations, the Escobars have made their uneasy peace with it. Tequila went north during Prohibition. Today, it’s mainly cocaine, pot and cheap labor. Tomorrow, it may be something else.

“It’s mostly the disturbances at night, early hours in the morning, that’s when they do their stuff, waking you up because you hear these sounds or the dogs are constantly barking,” he says. “Wherever there is a border, there are problems.”

Escobar is standing only a few feet from the water as he says this, at the rear of his parked truck. He motions to the spot where the National Guard set up camp two years ago to help deal with a surge of immigrant crossings. Then he points down to the fresh tracks left almost daily by the U.S. Border Patrol or, increasingly, the Texas Department of Public Safety — flush with cash now from a state Legislature that promises to secure the border because Washington won’t.

Here, at this precise moment on this April day, Escobar believes all the ramped-up security has paid off. Lately, he says, things seem to have calmed down on the borderland piece of his 600-acre ranch.

“I haven’t seen any traffic here in the last two years or so,” he says. “The highway patrol and border patrol are out here constantly.”

Armed confrontation

Escobar has a head full of stories about the unpredictable and sometimes startling nature of border living. Fully naked women have made the short swim from Mexico to his ranch. Boats of every kind have ferried people north through here. In the southbound traffic, he’s seen everything from television sets to tractor parts.

Escobar has quit counting how many times traffickers have rushed through his ranch toward Mexico with the law in hot pursuit. The last time, they bailed out of a Suburban fully loaded with marijuana. It landed in the Rio Grande and sat there for a day, with only the roof protruding from the water, before authorities could pull it out with giant cranes. His gate was run over by the traffickers, and then re-run over by the cops.

“I stopped fixing gates. I stopped putting them up,” he says. “They ram into them.” He’s also told his county commissioners to quit fixing his road, to just leave it in a state of disrepair.

“I climb real slow,” he says, grinning mischievously. “But the smugglers, when they come through here, they come in doing 50 miles an hour and they’ll bust their axles, they’ll bust their wheels.”

It’s one of the only ways Escobar can fight back. He’s pretty realistic about that. He doesn’t like the smugglers and the dopers. He wishes they didn’t use his property like it was their personal harbor. He wishes he didn’t have to feel so violated, so ripped off every time he pays his taxes. But what are his options?

He tells the story of an armed confrontation on his ranch — one of two he can remember. This one happened about two or three years ago, not long before the National Guard came and temporarily restored order. One night, his workers came to him and reported trouble down by the pump. They were trying to shut it off by 10 p.m. to meet state water-use regulations.

Two armed men told them to “forget it” — to leave and not come back that evening.

Escobar flashes a knowing look. He says one of the armed men told his workers, “get out of here, this is ours tonight.”

What were they to do? What about the pump? Escobar says he told his workers to just let it go until the diesel ran out. The next day his fields were covered in water, but everyone was still alive, and whatever operation the armed men had conducted was over and done with.

This is the dilemma Escobar fervently wants his interviewers to contemplate.

“What do you do? Do I run to the police and tell them, ‘Hey, go catch them, they’re there?'” Escobar asks. “They’re going to know who did it. They’re going to know who fingered them.”

Casting your lot with the bad guys doesn’t make much sense, either. Were he to agree to work with them — and he’s been asked plenty of times — the police would figure it out eventually. He’s got that speech down pat.

“You’ll get caught one of these days and then that’s it,” Escobar tells them. “I don’t want you to be telling the cops that I used to be in cahoots with you on this.”

He figures the system is working. No one in his family has ever been harmed despite years of living next to a patch of Mexico where mafia shootouts happen nightly and thousands have vanished without a trace.

He knows the code. It’s the code his ancestors used, and the one future Escobars will no doubt employ: “You just have to swallow your pride, sort of, and say, well you know what, just don’t bother us. Just leave us alone and we’ll leave you alone.”

Escobar admits it “may not sound too brave,” but who is going to come rescue him if he tattles?

Growing pensive, the rancher stops to let the words sink in. He swats at the incessant gnats that also find the river a big draw.

“What do you do?” he asks again. “Yeah we curse them, but that’s about as far ...”

He doesn’t get to finish the sentence. He is interrupted by a sudden disturbance on the water: A shout. Movement.

Escobar turns his head and looks upriver.

“Mira,” he says, lapsing into the language he learned from his parents. “Look.”

The rhythms and risks of border enforcement are captured in this mini-documentary following U.S. Border Patrol agents in Starr County.

"We are not policemen"

There is a large inflatable raft behind Escobar now. It is filled with people and they’ve just made an illegal landing on the U.S. river bank — his river bank, as far as the property rolls are concerned — perhaps a football field away. Escobar, 72, finds himself walking briskly through the brush with a reporter and photographer from The Texas Tribune. And with every step, the idea that ramped-up “border security” is denting the flow of illegal traffic here becomes more illusory.

The woods are thick in this direction, not like the clearing where the water pump sits. The immigrants seem to have been swallowed up in a thick grove of Carrizo cane, the tall, bamboo-like reeds that thrive in shallow waters. But they can’t be far. They didn’t just disappear.

The rancher stops and listens.

They are on the move now. And as they rustle through the thick brambles and thorny mesquite trees, the crunching sound beneath their feet gives them away.

There are roughly 15 in all. There are heading north, moving through the trees and brush as fast as they safely can. All appear to be adult men. One pulls his black shirt up to hide his face. Others don’t seem to notice, or maybe just don’t care, that they’re being watched. There’s a flash of white — from a small plastic grocery bag one is carrying. Otherwise they all appear to be traveling with nothing but the clothes on their backs and the ball caps on their heads. They are gone in seconds.

Two of the men stay behind, though. And now both are standing 35 feet away from Escobar in a grassy clearing between the cane-choked riverbank and the woods where the immigrants just disappeared. One of the men in the clearing is dressed in camouflage. The other is wearing a green shirt and cap that match the tropical vegetation. They have on life vests, and both are looking warily, uncertainly, at Escobar and his media friends. The rancher and his guests are looking just as warily back at them.

These are the coyotes — smugglers.

“Don’t take video,” the one in camouflage says to the owner of the property, not that ownership means anything in a moment like this.

Escobar responds in a conciliatory tone.

“We are not policemen,” he says in Spanish.

“Ah, good,” the smugglers answer. “Thank you.”

They visibly relax and take a few steps toward Escobar. They both look to be in their late teens or early 20s.

Escobar speaks again.

“They are just reporteros,” he says. Reporters. The word seems to give them reason to pause again and the one in camouflage repeats his demand, more politely this time, that the filming cease. And so it does.

With the cameras turned off and lowered, a brief conversation ensues. They want to know why they were being filmed. Escobar explains that he is the subject of an upcoming news feature story. They don’t seem to understand.

“I’m the rancher here.”

“Oh, the one with the pump?” the lead smuggler says.

“Yes, the one with the pump. They are here to do a story about me,” he responds.

Satisfied, they nod and start again toward the river. But before they disappear into the Carrizo cane, the camouflaged one can't resist the temptation to shape the narrative. He turns and says he wants Escobar and his friends to know that they’re moving Mexican workers through here, not drugs.

“It’s not the same thing. It’s people,” he says. “If it were drugs, we wouldn’t be talking to you.” Escobar promises to make that clear to the reporters, and the men turn and vanish into the thick reeds.

A smart plan

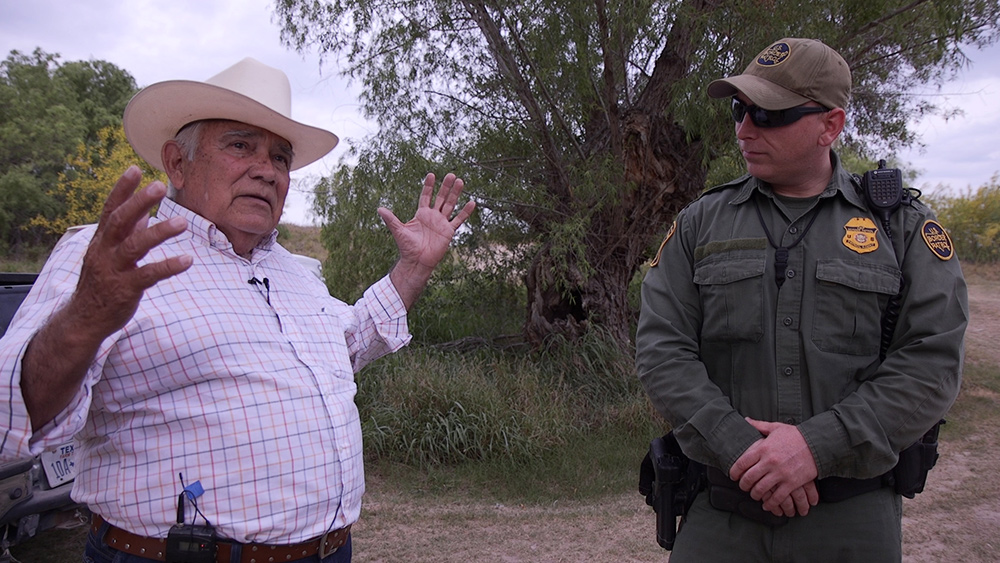

“The one with the pump” makes his way back to the clearing, to the rear of the truck, where he stood when the raft landed on the river bank. Before the sun goes down, the Border Patrol and two DPS troopers show up, but the immigrants and their coyotes are nowhere to be seen by then. Escobar tells the Border Patrol agent, who says his name is Serge, that he welcomes any and all law enforcement onto his ranch.

The rancher is equally adamant that he won’t be doing any law enforcement himself — just like he told the smugglers in person less than an hour earlier. It’s the code you follow around here if you want to stay alive.

“I’m not going to stand in their way and try to stop them,” he tells the agent.

Serge shakes his head back and forth.

“No,” he responds. “Smart plan.”

Ruperto Escobar with a Border Patrol agent on his ranch in Starr County in South Texas. His ancestors settled this area after getting a Spanish land grant in 1767TODD WISEMAN / THE TEXAS TRIBUNE

https://www.texastribune.org/2016/06...-art-survival/Support our FIGHT AGAINST illegal immigration & Amnesty by joining our E-mail Alerts at https://eepurl.com/cktGTn

Similar Threads

-

Border Rancher Warns of Cartel Border Takeover on U.S. Soil

By Newmexican in forum Videos about Illegal Immigration, refugee programs, globalism, & socialismReplies: 0Last Post: 08-29-2015, 09:35 PM -

Border Rancher that was sued by Ill coming up FOX

By topsecret10 in forum General DiscussionReplies: 9Last Post: 02-21-2011, 05:09 PM -

AZ: A Rancher's Personal Border Battle

By bigtex in forum illegal immigration News Stories & ReportsReplies: 4Last Post: 07-22-2010, 01:51 PM -

FoxNews Reports on Border Rancher

By Rai7965 in forum illegal immigration News Stories & ReportsReplies: 1Last Post: 05-28-2010, 09:19 PM -

Interview with border rancher

By tiredofit in forum Videos about Illegal Immigration, refugee programs, globalism, & socialismReplies: 0Last Post: 05-28-2010, 10:40 AM

LinkBack URL

LinkBack URL About LinkBacks

About LinkBacks

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Oklahoma House passes bill making illegal immigration a state...

04-19-2024, 05:14 AM in illegal immigration News Stories & Reports